- ● homepage

- ● archives

- ● restoration

- ● books

- ● big banners

- ● post board

- ■ neo's search

- ■ about us

- ■ 게재방법 안내

- 개인정보처리방침

- [email protected]

- Tel. 02_335_7922

- Fax. 02_335_7929

- 10:00am~04:30pm

- 월요일~금요일

- 3/3(월) 대체공휴일

The Same Yet Different 하나이면서 둘인 一而二

정주영展 / CHUNGZUYOUNG / 鄭珠泳 / painting 2010_0311 ▶ 2010_0509 / 월요일 휴관

● 위 이미지를 클릭하면 네오룩 아카이브 Vol.20080321d | 정주영展으로 갑니다.

초대일시_2010_0311_목요일_06:00pm

관람시간 / 11:00am~06:00pm / 월요일 휴관

몽인아트센터_MONGIN ART CENTER 서울 종로구 삼청동 106번지 Tel. +82.2.736.1446~8 www.mongin.org

동시대적 정신의 원형을 찾아서 ● 「하나이면서 둘인(一而二)」이라고 칭한 정주영의 이번 전시는 바위가 주가 되는 암산(岩山)의 모습을 보여주었던 2006년의 개인展 『활경(活景)』과 산(山) 그림의 또 다른 연장선상에서 토산(土山), 즉 흙과 나무가 어우러진 숲의 부드러운 풍경을 대비적으로 보여주었던 2007년의 개인展 『생생화화(生生化化)』를 아우르는 결과물이다. 독일 유학시절 초기, 공원의 풍경을 그리는 것으로부터 시작된 그의 회화 작업은 18세기 중반의 단원(檀園) 김홍도(金弘道)와 겸재(謙齋) 정선(鄭敾)의 진경산수화(眞景山水畵)를 재해석하는 과정을 거쳐 오늘날 작가 자신과 대면하고 있는 현실 속의 풍경을 바라보는 태도로 이어져왔다. 이 오랜 작업 여정을 관통하는 것은 '오늘날 풍경을 바라본다는 것은 어떤 태도인가'라는 질문이며, 이번 전시에 보여지는 일련의 작업에서는 이 질문에 대한 고민의 흔적이 드러나고 있다.

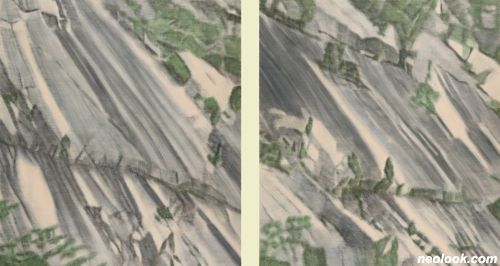

- 정주영_인왕산9_마천에 유채_200×800cm_2009

- 정주영_인왕산8-1, 인왕산8-2, 인왕산8-3_마천에 유채_각 145×135cm_2008

수도 없이 인왕산을 지나치고, 인왕산을 바라보며, 작은 드로잉에서부터 8미터 너비의 거대한 회화 작업에 이르기까지 인왕산의 다양한 모습을 재현해내는 동안 줄곧 정주영을 전율케 했던 것은 「인왕제색도(仁王霽色圖)」(1751)를 그리던 당시 정선의 눈 속에 담겼던 인왕산을 오늘 마주하며 자신의 눈으로 바라보고 있다는 사실이었다. 그리고 이러한 인식은 단지 인왕산에만 해당되는 것이 아니었다. 정주영 스스로 밝히고 있듯이, 인왕산을 바라볼 때 비 온 뒤 안개 속으로 드러나는 「인왕제색도」 속 인왕산의 모습이 겹쳐지듯이, 시간과 계절에 따라 서로 다른 면면을 드러내는 북악산의 모습 또한 옛 그림 속에서 그 산이 보여주었던 다양한 풍경의 층위로 다가왔던 것이다. 이러한 전율은 배를 타고 한강 주변을 그렸던 정선을 좇아 그의 그림에 등장하는 산을 지표(指標)로 삼아 실제 한강 주변을 그린 일련의 풍경을 통해 화면으로 옮겨졌다. 그 옛날 선인(先人)들의 화첩에 담긴 그림들에 마치 나침반처럼 등장하는 산을 실제 장소에서 보고 그림으로 옮기는 작업을 하면서 정주영은 시간의 흐름 속에서도 여전히 본래의 자리를 지키고 있는 산에서 새삼 영구한 지속성의 표상을 발견하게 된다. 이 변치 않는 산의 존재는 정주영의 화면에 하나의 지표로 제시되며, 나아가 모든 것의 존재를 가능케 하는 근원적인 힘을 발원시키는 하나의 상징으로 자리하게 된다. 그리고 '오늘날 풍경을 바라본다는 것은 어떤 태도인가'라는 작가의 질문은 옛 선인의 시선과 자신의 시선을 중첩시키는 대상으로서의 산, 불변하는 지표로서의 산을 그리는 행위를 통해 정리되어 간다. 결국, 김홍도와 정선의 진경산수화에 대한 작업을 해왔던 정주영에게 있어 250여 년이라는 시간의 간극을 무색하게 했던 이 존재론적 전율은 그의 작업 여정에 또 하나의 의미를 더하는 계기가 되었던 것이다.

- 정주영_인왕산6_마천에 유채_205×280cm_2008

이러한 실존적 인식을 바탕으로 하여 변하지 않는 원형(原型)으로서의 산을 담고 있는 풍경을 자신의 눈, 자신의 몸으로 바라보는 경험은 '그리는 행위'라는 몸의 궤적을 통해 화면 위로 고스란히 옮겨진다. 설치미술과 개념미술에의 관심을 뒤로 하고 회화에 천착하기 시작한 이래 고집스럽게 커다란 캔버스를 고수해온 정주영에게 있어 회화는 단순히 이미지를 재현한 화면(畵面)이 아니라 자기 분석과 반성의 궤적을 옮겨 놓은 행위의 장(場)이었다. 이것은 정주영 스스로가 '그린다는 것'을 '회화가 숙명적으로 가지고 있는 "몸", 즉, 캔버스와 그것의 물리적 부피뿐만 아니라 그로 인한 그리는 행위 속의 작용과 반작용'과 연관 짓고 있다는 점에서도 드러난다. 김홍도나 정선의 그림에 대한 작업을 하던 시기에도 화면과 그리는 행위와의 관계는 정주영의 작업에서 간과할 수 없는 부분이었지만, 자신의 눈(몸)으로 본 것을 스스로의 몸을 움직여 그리는 행위, 그리고 이것을 끊임없이 반복해가는 수행과도 같은 과정은 실경(實景)을 경험한 이후의 작업에서 더욱 진지하게 드러난다. 더불어 자신이 발 딛고 서있는 3차원 공간의 경험, 즉, 자신을 둘러싸고 있는 현실에 대한 인식은 선인들의 2차원 평면을 대면한 경험을 옮기던 추상적인 붓질, 주로 하늘이나 물을 암시하는 여백 부분을 추상적으로 구축하던 붓질을 떠나 보다 사실적인 재현을 가능케 하는 구체적인 붓질로 변화해가는 전환점을 마련하게 한다.

- 정주영_인왕산7_마천에 유채_140×270cm_2008

결국, 정주영의 작업은 실제 풍경을 대하는 정주영의 작가적 태도의 반영이며, 시간의 흐름을 초월하여 실제 풍경 속에서 변하지 않고 존재하는 산과 조우한 순간 깨어난 경이로운 감정의 회화적 번안이다. 시간을 초월한 산과 대면한 나, 그리고 이 순간적인 전율에 대한 존재론적 접근은 세계 속의 나, 현실 속의 나를 인식하게 하고, 다시 나를 둘러싼 현실과 세계를 재인식하고 그 속의 모든 존재들 간의 고리를 연결하려는 시도로 확장된다. 그리고 이 시도의 근저에는 관념이 아닌, 자신의 눈(몸)으로 보고 생각하는, 생생한 경험과 삶에 기초하는 현실의 인식, 동시대성의 인식이 자리 잡고 있다. 이 현실적이고 실재적인 인식의 과정에 개입하는 작가의 수행적 행위는 화면 위에 작가 자신의 존재론적인 욕구를 오롯이 체화(體化)시켜 드러내며, 이것은 18세기 진경산수화를 추동(推動)시켰던 인식의 21세기적 변용으로 읽혀진다. 이렇듯 변하지 않는 것처럼 보이는 산의 모습 속에서 '고정적인 것'으로서가 아니라 '나날이 새로워지고 변화하는[生生化化]' 동시에 '하나이면서 둘인[一而二]' 자연의 모습, 즉 '변화무쌍하게 끊임없이 생동하는 살아있는 원형'으로서의 풍경을 인식하고 이것을 회화를 통해 현재에 위치시키려는 정주영의 태도는 '풍경의 단순한 재현'이 아닌 '진경의 관점에 대한 재해석'이며, 나아가 '동시대적 정신의 원형 찾기'로 자리매김될 수 있을 것이다. ■ 김윤경

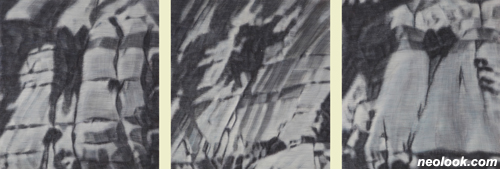

- 정주영展_몽인아트센터_2010

- 정주영展_몽인아트센터_2010

In Search of an Archetype for Contemporaneity ● In 2006, Zuyoung Chung showcased a series of paintings of craggy mountainous terrain in a solo exhibition entitled 『Mountains before Your Eyes』. The following year, her show, 「Mountains Eternally Present」, which focused on the "softness" of landscape portraying earth and trees, was a striking contrast. This exhibition, entitled 『The Same Yet Different』, is, in many ways, a dialectic outcome of these two prior shows. During her studies in Dusseldorf, Germany, Chung first started to display an interest in small park landscapes in her work. This interest has progressed towards revisiting and reinterpreting the mid-eighteenth century Korean True-View landscape paintings (chin'gyong sansuhwa) of Kim Hong-do and Jeong Seon, and recognizing her renewed interest in confronting this "real view." What has been consistent in this journey in her work is the persistent question, "what attitude does one hold nowadays to gaze upon the landscape," to which the series of paintings in the exhibition forms a response. ● In numerous trips to Mt. Inwang, beholding the mountain, and representing it in her work through small drawings to large-scale paintings, Chung seems enraptured by the fact that she is confronting the very same mountain that was before Jeong Seon's eyes when he painted his masterpiece, 「After Rain at Mt. Inwang (Inwangjesaekdo)」 in 1751. Yet this is not only the case with Mt. Inwang. As Chung herself acknowledges, her view of Mt. Inwang is not only informed by her impression of viewing the same mountain in Jeong Seon's 「After Rain at Mt. Inwang」, but also beholding the sight of other mountains as depicted in other paintings of the Korean traditional landscape genre. This wonderment is transmitted to the painterly surfaces of a series of paintings by Chung depicting views along the Han River that follow Jeong Seon's precedent. In the paintings of her predecessors, the mountains appear as if they are points on a compass. While looking at the mountain in order to paint it, Chung is able to discover an emblem of the eternal continuum of the mountain that still exists in situ, overriding the lapse of time. The enduring existence of the mountain is presented as an index on Chung's pictorial plane, and finds its own level as a symbol of the fundamental force from which the existence of all nature originates. Thus, the artist's question, "what attitude does one hold nowadays to gaze upon the landscape," is resolved by Chung by painting the mountain as an object whereupon the vision before her eyes overlaps with those of her predecessors to capture the indexical "truth" or reality of the mountain. By revisiting and reinterpreting the True-View landscape paintings of Kim Hong-do and Jeong Seon, the moment of experiencing the actual mountain coincides with seeing the Korean traditional painting in her mind's eye to produce the frisson of recognition in her work. This ontological wonderment has surged across a time gap of more than 250 years to provide significant momentum in shaping the course of Chung's oeuvre. ● In terms of existential recognition, Chung's experience of looking into a view of the mountain as an eternal archetype through her own eye and corporal presence is wholly transferred to the pictorial plane through the bodily trace enacted by the "act of painting." While Chung worked primarily in installation art and conceptual art prior to her studies in Germany, her interest has shifted exclusively to painting to focus on the large-scale canvas. The medium itself provides a field of action whereby the trace of her self-analysis and self-reflection can be transferred, not merely a pictorial plane to represent images. This is clarified by Chung's statement that "to paint" can be understood in conjunction with the painting's intertwined fate with the "body," that is, the canvas and its physical volume in tandem with the action/reaction involved in the act of painting itself. This relationship between the pictorial plane and the act of painting as she revisits and reinterprets the paintings of Kim Hong-do and Jeong Seon is crucial to Chung's project and should not be overlooked. But perhaps even more significant is the performative process of the act of painting what she sees with her own eye (body), in that it literally embodies Chung's experience of the real view around her. Moreover, the experience of a three-dimensional space, that is, conveying the reality around her, proves to be a critical turning point away from merely abstract brushstrokes of reinterpreting the predecessors' paintings towards the artist's desire to present her own "real view." ● Chung's body of work is a reflection of her attitude in attaining a real view of landscape as an artist, as well as a painterly translation of her wonderment at the phenomenon of encountering the eternal mountain, pre-existing in both Jeong Seon's painting and in reality, beyond the scope of chronological time. An ontological approach to the ego facing this eternal mountain accompanied by such fleeting amazement leads to a recognition of the ego in the world and the ego in reality and then, in turn, the world and reality around the ego, extending towards an attempt to connect every being within it. At the basis of this attempt is where the recognition of reality and contemporaneity lies, stemming from corporal thinking and the experience of life. Chung's performative act of intervening in the realistic and actual process of recognition embodies her ontological desire on a picture plane. These works represent a twenty-first century transfiguration of the initial impetus of True-View landscape painting of the eighteenth century. Chung attempts to pursue and recognize a view of nature that is "eternally present before your eyes" as well as "same yet different," that is, the landscape as "a constantly vibrant kaleidoscopic archetype," to locate it here and now, in the present. It is thus not "a mere representation of landscape," but rather "a reinterpretation of the standpoint of True-View" and "a search for an archetype for contemporaneity." ■ Yunkyoung Kim

Vol.20100312f | 정주영展 / CHUNGZUYOUNG / 鄭珠泳 / painting