- ● homepage

- ● archives

- ● restoration

- ● books

- ● big banners

- ● post board

- ■ neo's search

- ■ about us

- ■ 게재방법 안내

- 개인정보처리방침

- [email protected]

- Tel. 02_335_7922

- Fax. 02_335_7929

- 10:00am~04:30pm

- 월요일~금요일

- 3/3(월) 대체공휴일

잃어버린 줄 알았어! I Thought I Lost It!

엄정순_딩 이_시오타 치하루展 2024_0903 ▶ 2024_1003 / 일,월요일 휴관

별도의 초대일시가 없습니다.

주최 / 학고재

관람시간 / 10:00am~06:00pm / 일,월요일 휴관

학고재 본관 Hakgojae Gallery, Space 1 서울 종로구 삼청로 50 Tel. +82.(0)2.720.1524~6 www.hakgojae.com @hakgojaegallery www.facebook.com/hakgojaegallery

학고재 신관 Hakgojae Gallery, Space 2 서울 종로구 삼청로 48-4 Tel. +82.(0)2.720.1524~6 www.hakgojae.com @hakgojaegallery www.facebook.com/hakgojaegallery

학고재 오룸 Hakgojae OROOM online.hakgojae.com

잃어버린 줄 알았어! ● 『잃어버린 줄 알았어!』는 "우리가 꿈꾸는 탄력적인 사회공동체를 만들기 위해 예술과 건축은 어 떤 사회적 합의에 기여할 수 있는가"를 조명해 보는 포럼이자 전시이다. 아울러 예술의 공동체 정 신과 사회적 포용성 등 예술과 사회의 관계항들을 다시 생각해 보는 아이디어의 플랫폼이다. ● 이 프로젝트가 "포럼으로서의 전시", "전시로서의 포럼"을 지향하는 것은 오랫동안 현대미술과 건축이 추구해 왔던 특정한 개념이나 형식, 스타일 중심의 엘리트적 실천으로부터 한발 물러나, 인류가 풀어야 할 다양한 형태의 '물려받은 상처'(inherited wound)들을 비롯하여 정치적, 사회적, 생태학적 숙명들을 회고하고, 다른 한편으로는 이를 더 기억하기 위함이다. ● 이 프로젝트가 제안하는 예술의 공동체 정신이란 예술과 사회의 관계론적 함의(relational implications)를 말한다. 즉 예술이 개인이나 공동체의 역사와 기억, 사회적 시스템 사이에서 어떤 연대 의식을 형성하고 사회적 합의에 참여하는지에 대해 토론한다. 앞에 언급한 '물려받은 상처' 란 개인이나 공동체, 국가에 이르기까지 다양한 사회적, 역사적 매듭들을 포함하며, 부지불식간에 발생하는 수많은 우발적이거나 기획된 폭력으로부터 파생된 개인적, 공동체적 파괴의 사슬을 말한다. ● 예술은 국경이나 이질 문화를 초월하여 인간에 대한 존엄성을 우선적으로 선언하고 주장하는 표 현공간이다. 아울러 배타성을 경계하는 자유와 상상력의 산물이다. 우리의 생생한 경험과 절망, 기억을 개별적, 집단적으로 묶어내고, 개인과 집단을 소통하게 하는 예술과 건축의 가능성은 그것의 메타 사회적 기능에서 나온다. ● 과거 모더니즘이 주창했던 선명성과 파편화는 과거와 미래, 남과 북, 진보와 퇴보, 급진과 보수를 가르고 결별시키는 방법으로 사용되었다. 그러나 생태학적으로 고통스러운 변화들이 부지불식간에 일어나는 오늘날의 현실을 고려할 때, 그러한 파편화된 담론의 항해 기술은 유효한 방향을 제 시하지 못한다. 따라서 이 포럼은 급했던 걸음을 멈추고 우리들의 판단력이 호소하는 감지 장치들을 다시 점검해 보기 위한 협의체 역할을 하고자 한다. ● 이번 프로젝트의 초대 예술가는 중국의 딩 이(丁乙), 일본의 시오타 치하루(塩田千春), 한국의 엄정순(嚴貞淳)이다. 이 예술가들의 공통점은 인간이 숙명적으로 안고 살아가는, 매우 암시적이지만 도피할 수 없는 자아정체성에 대한 도전과 실천을 주제로 한다. 그리고 예술이 사회적 변화와 포용성에 대하여 어떻게 수용, 중재, 대응해야 하는가에 대하여 발언한다. 특히 동기가 분명한 민주화된 오늘날의 관객들이 어떻게 예술, 도시, 건축을 재발견해야 하는가를 안내하는 맥락들을 짚어본다. 참가 예술가들은 또 급속한 기술 발전을 바탕으로 성장한 사회적 시스템이 초래한 인간의 부재와 생태적 위기를 진단하고 검증한다. 특히 우리가 학습하지 않는 이데올로기와 학습되지 않는 기억에 대하여 자기성찰의 목표를 찾는다는 점에서 중요한 맥락을 찾을 수 있을 것이다. 동아시아 지역의 한국, 중국, 일본 등 3개국의 예술가들은 오랫동안 서로 이웃하면서 상대방에 대 한 다양한 관점을 제안하고 상호 진단하며, 예술을 통해 자신의 정치, 사회, 문화적이고 생태학적 인 언어들을 개발하고 실천해 왔다. 프로젝트에 참가한 예술가들은 사회적 소수나 약자의 위치에 있는 개인을 비롯하여 사회적 공동체의 역사를 지탱하는 시대정신이나 기억을 시각문화적 문맥으로 실천해 오고 있다. 이는 특정 국가나 지역의 협소한 지정학적 이슈나 관계항들을 언급하는 것이 아니라, 예술의 존재론적 본질에 대해 답하고 또 제안해 온 예술가들이라는 사실이다. 아울러 이 같은 주제들을 연구해 오거나 관심을 가진 비평가와 큐레이터, 건축가, 학자, 도시계획자 등을 '연구자(researcher)'로 초빙하여 포럼을 진행한다. 포럼에서 발표하고 제안한 내용들은 전시 기간 중 단행본의 책으로 발간할 예정이다.

- 딩 이Ding Yi_십시 2024-13_참피나무에 아크릴채색, 목판_120×120cm_2024

- 딩 이Ding Yi_십시 2022-10_참피나무에 아크릴채색, 목판_240×240cm_2022

중국 예술가 딩 이는 1986년부터 40년 가까이 수학적 기호를 연상케 하는 십자(+)와 격자(x)를 표현 매체로 설정하여 1980년대 이후 중국 현대미술사에서 기하학적 추상의 선구자가 되었다. 그는 문화혁명 이후 1980년대부터 급속하게 등장한 아방가르드 운동의 실천적 1세대에 해당한다. 당시 신세대 현대미술가들은 문호 개방과 더불어 서구 현대미술의 영향을 강하게 받거나, 반대로 중국의 문화적 전통을 다시 들여다보고 중국성을 재발견하는 데 집중했다. 이와는 반대로 딩 이는 서구 영향도, 중국성에도 거리를 둔 채 예술 자체가 호소하거나 진단하는 본질적 문제를 질문하면서 자신만의 답을 찾아가고 있었다. 당시 젊은 예술가들은 새로운 것 자체를 가치로 보았으며, "더 과격하게, 더 실험적으로"를 외치던 시절이었다. ● 그는 다수의 젊은 예술가들이 더 크고 의미 있는 것들을 찾아 나설 때 오히려 의미 없고 하찮은, 아무도 관심을 두지 않는 수학기호와 같은 "+", "x"를 일종의 표현과 전달 매체로 활용하여 추상 회화를 시작하였다. 모두가 거대한 '의미'를 찾던 시대에 '무의미'를 대안으로 제시하면서 역설적으로 거부 의사를 표현한 것이다. 그가 시작한 추상예술은 문화혁명기에는 자본주의의 퇴폐예술 로 간주하여 금지되었던 장르이다. 그러나 그는 추상의 메타포가 내포하는 메시지들을 시대를 읽고 증언하며, 포용하는 표현적 대안으로 설정하였다. 그의 예술은 중국의 개혁개방에 따른 사회적 변화, 경제 발전, 대도시화의 모습들을 다양한 주제와 구성, 색상을 활용하여 기억하고 저장하는 메신저 역할을 했다.

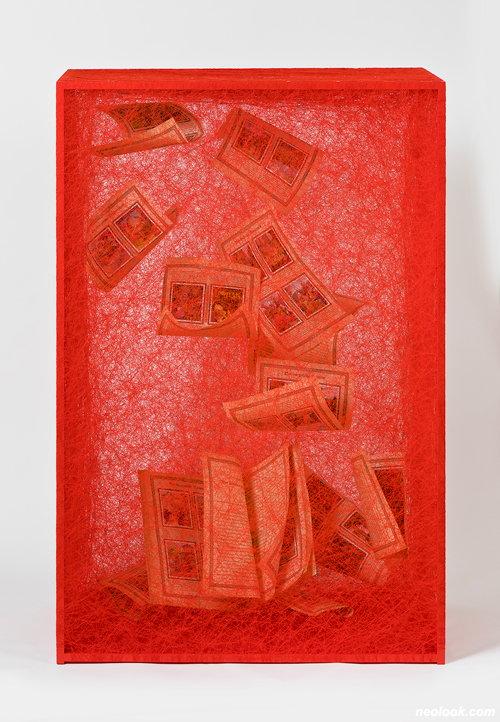

- 시오타 치하루Shiota Chiharu_State of Being (Book)_메탈 프레임, 책, 실_120×80×45cm_2023

- 시오타 치하루Shiota Chiharu_Endless Line_캔버스에 실_162.2×130.3cm×3_2014

시오타 치하루는 1996년부터 베를린에 거주하고 있으며, 퍼포먼스와 실을 사용하는 설치미술가로 잘 알려져 있다. 그녀가 집중적으로 탐구하고 표현하는 메시지들은 특정 공간과 그 공간을 차지하는 물질과의 상호 연관성을 연구한다. 특히 우리의 일상을 지배하는 절실한 기억이나 신체, 경계영역, 소외 등 매우 개별적이면서도 사회적 상관관계를 질문하는 맥락들을 섬세하게 노출하고 해석한다. ● 붉은색, 검은색, 흰색 등의 실이나 호스를 활용하는 그녀의 설치작품은 작품이 놓이는 공간(방)에 대한 설정이 매우 중요하다. 실을 활용한 그녀의 설치작품에 자주 등장하는 소품들은 열쇠, 창틀, 헌 옷, 신발, 보트, 여행 가방, 플라스틱 튜브와 같은 일상적이면서 예술가의 개별적, 또는 집단적 기억과 연결된 구체적 물건들이다. 작품에 등장하는 색상과 소재는 중요한 암시적 요소이며, 이러 한 소품들 가운데는 생명을 상징하는 붉은 피 색깔의 실이나 소품들이 다양하게 얽혀 있다. 이러 한 구성과 전시에 사용되는 작은 소품들은 삶의 주변이나 우리들의 DNA에 살아서 꿈틀거리는 기억들을 연상하도록 한다.

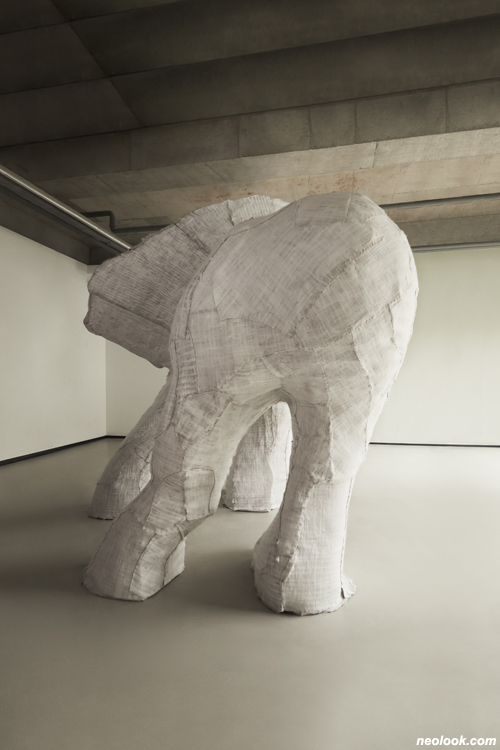

- 엄정순_코 없는 코끼리_철판, 태피스트리_300×274.1×307.4cm_2022

- 엄정순_코끼리걷는다 - 물과 풀이 좋은 곳으로 3_캔버스에 아크릴채색, 오일 스틱_228×362cm_2021

전시장에서 절대로 금지된 터부는 천재적 예술가들의 손을 거쳐 제작된 숭고한 미학적 세례품인 예술 작품을 관객들이 만지는 것이다. 그러나 예술가 엄정순은 역으로 관객들에게 작품을 만질 수 있도록 권유하면서 작가가 설정한 주제로 참여를 유도한다. 가령 시각장애인들에게 코끼리를 만지는 것은 코끼리를 보는 것이다. 불교 경전인 『열반경』에 "장님 코끼리 만지기"라는 말이 있다. 코끼리는 손의 감각으로 파악할 수 있는 작은 물체가 아닌 거대한 볼륨을 가진 짐작 불가능한 물 체이다. 전체를 만질 수 없는 거대한 물체는 만지는 부위의 특성만 손으로 볼 수 있다. 본다는 것 과 보지 못하는 것 사이의 차이는 하늘과 땅만큼 크다. 예술이 소수자들을 돕고 치유할 수 있는 사회적 포용성은 절대적이며, 그 사회적 합의를 도출하는 과정 또한 예술의 사회적 동의나 참여와 관계가 있다. 보는 것과 보지 못하는 것 사이의 사회적 격리는 거대한 것이며, 소수자를 돕는 제도적 장치가 없으면 불가능하다. ■ 이용우

I Thought I Lost It! ● I Thought I Lost It! is a project in the form of forum and exhibition that examines how art and architecture can contribute to the social consensus to create the resilient social communities we envision. This project serves as a platform for re-evaluating the interplay between art and society, focusing on themes such as communal engagement and social inclusiveness within artistic practices. ● This project, conceptualized as both a 'forum as an exhibition' and an 'exhibition as a forum,' seeks to break away from the elitist focus on specific concepts, forms, and styles that contemporary art and architecture have long pursued. Instead, it aims to critically reflect on the myriad of "inherited wounds" that humanity must confront—encompassing political, social, and ecological challenges—while endeavoring to preserve the individual and collective memory of these issues. ● The community spirit of art advocated by this project pertains to the relational implications between art and society. It engages in a verification of how art fosters solidarity within the historical and mnemonic frameworks of individuals or communities, and how it contributes to social agreements. The term "inherited wounds" encompasses a range of social and historical entanglements impacting individuals, communities, and nations. It refers to the continuum of personal and collective trauma resulting from both inadvertent and intentional acts of violence, which frequently occur in an unconscious manner. ● Art constitutes a realm of expression that upholds and asserts human dignity, transcending geographical and cultural boundaries. It is also a product of freedom and imagination, which guard against exclusivity. The capacity of art and architecture to forge spaces that intertwine our individual and collective experiences, sorrows, and memories stems from their meta-social function, which fosters communication and connection among individuals and groups. ● Historically, modernism's emphasis on clarity and fragmentation was used to draw distinctions between the past and the future, the North and the South, progress and regression, and radicalism and conservatism. However, in light of the current ecological crises and profound transformations, such fragmented discourses no longer provide a viable direction. This forum, therefore, aims to serve as a consultative platform to pause the momentum and reevaluate the factors that influence our judgments. ● The invited artists for this project are Oum Jeongsoon from Korea, Ding Yi from China, and Shiota Chiharu from Japan. These artists share a common theme of challenging and exploring the implicit yet inescapable self-identity that humans experience as a fate. Their works focus how art should engage with, mediate, and respond to social change as well as inclusiveness. Additionally, the project investigates how contemporary, motivated, and democratized audiences should reassess art, urban spaces, and architecture. The participating artists also diagnose and validate the human absence and ecological crises subtly imposed by social systems driven by rapid technological advancements. This provides a crucial framework for reflecting on ideologies we have yet to learn and memories we have yet to acquire. ● Artists from three countries in East Asia—Korea, China, and Japan—share a long history of mutual influence and dialogue, proposing and critically assessing diverse perspectives on one another. Through their art, they have developed and articulated their own political, social, cultural, and ecological discourses. The artists participating in this project embody the zeitgeist and collective memories that shape the historical narratives of social communities, including those in marginalized or vulnerable positions, within a visual-cultural framework. This approach transcends narrow geopolitical issues or specific regional relationships, focusing instead on the ontological essence of art. Additionally, critics, curators, architects, and urban planners with research interests in these themes are invited to participate in the forum as 'researchers.' The presentations and insights shared during the forum will be compiled and published in a book during the exhibition period. ● Chinese artist Ding Yi emerged as a pioneer of geometric abstraction in the history of Chinese contemporary art, utilizing the cross (+) and grid (x) symbols—reminiscent of mathematical notation—as his primary expressive medium for nearly four decades, beginning in 1986. He belongs to the first generation of the avant-garde movement that rapidly developed in the 1980s following the Cultural Revolution. During this period, the new generation of contemporary artists were either significantly influenced by Western contemporary art due to China's opening or focused on revisiting Chinese cultural traditions to reaffirm Chinese identity. In contrast, Ding Yi distanced himself from both Western influences and the quest for a distinct Chinese identity. Instead, he engaged with the fundamental questions that art itself poses or addresses, and sought his own resolutions. At that time, young artists valued novelty and endorsed "more radical and more experimental" approaches. ● He began his journey into abstract painting in 1986 by using seemingly trivial and neglected mathematical symbol-like signs "+" and "x" as mediums of expression and communication. This approach starkly contrasted with the trend of many young artists who were seeking grand and meaningful themes. By proposing meaninglessness as an alternative in an era obsessed with finding profound meanings, he paradoxically conveyed his rejection of such pursuits. The abstract art he pioneered was considered decadent and banned during the Cultural Revolution as a form of capitalist art. However, he redefined abstract metaphors as a means to interpret and reflect on the times, using them as an expressive alternative. His art served as a messenger, documenting and reflecting on the social changes, economic development, and urbanization in China through diverse themes, compositions, and colors. ● Shiota Chiharu, who has been based in Berlin since 1996, is renowned for her performance and installation art that employs threads. Her work explores the interplay between specific spaces and the materials within them, delicately exposing and interpreting themes such as memory, the body, boundaries, and alienation, while blending individual and social connections. ● Her installations, often created with threads or hoses in colors like red, black, and white, emphasize the significance of the space in which they are displayed. Everyday objects featured in her work—such as keys, window frames, old clothes, shoes, boats, travel bags, and plastic tubes—are connected to personal or collective memories. The colors and materials, particularly red, which symbolizes lives, are intricately interwoven with these objects and threads. These small objects and their arrangements evoke memories that seem to resonate with life around us or within our DNA. ● In contrast to the common art-world taboo against touching artworks, artist Oum Jeongsoon invites viewers to touch and interact with her works, encouraging participation in the themes she explores. For instance, for visually impaired individuals, touching an elephant provides a sensory experience akin to encountering its presence. This idea is encapsulated in the Buddhist phrase "As if a blind person touches an elephant" from the Nirvana Sutra. An elephant is a massive and complex entity, that represents a profound contrast between seeing and not seeing, emphasizing the importance of social inclusiveness in art. Art's capacity to support and heal marginalized groups, and its role in fostering social consensus through participatory engagement, are central to Oum Jeongsoon's practice. Oum Jeongsoon's concept of social inclusiveness extends beyond mere tolerance or compromise; it involves creating institutional mechanisms and participatory opportunities for marginalized groups. Her artistic practices and research are grounded in reality, not just imagination. For visually impaired individuals, the abstract or imagined trunk and ears of an elephant differ significantly from the perceptions of sighted people. Her project, Another Way of Seeing, integrates art with social engagement, using imagination to explore new perspectives. ● Historically, when an elephant was first brought to Korea 600 years ago, a government official mocked and mistreated it due to its unusual appearance, eventually being killed by the elephant's trunk. The elephant was then exiled to a remote island. Upon learning of this, King Sejong decreed that the elephant be sent to a location with good water and grass to prevent further suffering. This event, recorded in The Veritable Records of King Sejong, underscores the irony that art created by those who have never seen an elephant— socially marginalized individuals—can become a powerful symbol of social participation and inclusiveness. The creation of an elephant without a trunk by those who have never seen one metaphorically challenges notions of power or hierarchy. ● The works of participating artists capture the interaction of social anthropological messages such as time, history, individual and collective memory, evolution, progress, inclusiveness, and exclusiveness. They remind us that art plays a crucial role in addressing societal issues related to architecture, urban development, technology, and the environment while intervening in and conveying social meanings. These artists reflect on the loss of communal spirit in rapidly urbanizing East Asia since the late 20th century and evoke the impact of consumerism and urbanization on the small, beautiful memories of city life. ■ 이용우

Vol.20240908b | 잃어버린 줄 알았어! I Thought I Lost It!展