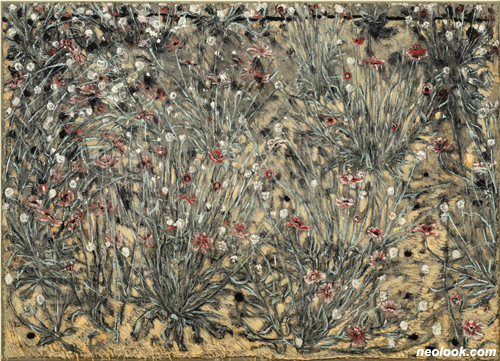

- ● homepage

- ● archives

- ● restoration

- ● books

- ● big banners

- ● post board

- ■ neo's search

- ■ about us

- ■ 게재방법 안내

- 개인정보처리방침

- [email protected]

- Tel. 02_335_7922

- Fax. 02_335_7929

- 10:00am~04:30pm

- 월요일~금요일

- 3/3(월) 대체공휴일

REFLECTION

유근택展 / YOOGEUNTAEK / 柳根澤 / painting.installation 2023_1025 ▶ 2023_1203 / 월요일 휴관

● 위 이미지를 클릭하면 네오룩 아카이브 Vol.20221113j | 유근택展으로 갑니다.

유근택 홈페이지_www.geuntaek.com 인스타그램_@yoogeuntaek

초대일시 / 2023_1025_수요일_04:00pm

관람시간 / 10:00am~06:00pm / 월요일 휴관

갤러리 현대 본관 GALLERY HYUNDAI 서울 종로구 삼청로 14(사간동 82-1번지) Tel. +82.(0)2.2287.3500 www.galleryhyundai.com

유근택, 또는 회화의 반투명성에 관하여 ● 유근택의 회화 작품을 처음 본 것은 2000년 가을이었다. 이따금 방문하는 교외에 위치한 국립현대미술관 과천관에서 열린 『젊은 모색 2000-새로운 세기를 향하여』(2000)라는 그룹전에 전시된 6점의 수묵화 연작 「긴 울타리」(2000)가 그것이다. 나는 기민한 감식안을 지닌 사람은 아니지만, 이때만큼은 굉장한 작품을 보았다고 즉시 생각하였고 고양감을 누를 길이 없었다. 이후 이 화가에 대한 극찬하는 내용을 담은 평론을 세 번이나 썼다. 이번에 쓰면 네 번째가 된다. 외국 작가에 대해 여러 번 글을 쓰는 것은 이례적인 일이다. 그래서 이번에는 글쓰기 취향을 조금 바꿔 반세기가량 한국의 바로 옆 나라에서 비평 활동을 지속해 온 나의 비평의 배경과 기준을 다시금 표명하면서, 왜 유근택의 회화가 나에게(우리에게) 특별하고 귀중했는가를 밝히고 싶다. 기억이 가물가물 흐려지고 있는데 반세기를 되짚어 보는 일이므로, 사실관계가 어긋난 내용이, 마치 대나무 바구니에서 낱알이 쏟아지듯 등장한다 해도 너그러이 이해해 주길 바란다.

- 유근택_창문_한지에 수묵채색_146×103cm_2022

- 유근택_말하는 정원_한지에 수묵채색_149×101cm_2020

내가 미술비평가 활동을 시작한 1970년의 일본은 구질서를 비판・부정하는 전위적인 분위기가 한창 고조되어 두 가지 쟁점이 치열하게 부딪치는 상황이었다. 한편으로는 『도쿄비엔날레 '70』의 기획을 맡은 비평가 나카하라 유스케(中原佑介)가 1960년대부터 전개되어온 복잡다단한 반예술의 동향을 동시대 서구의 최첨단 경향을 참조하면서 탈감정화・탈지역화하여 전통예술의 방법론에 따르지 않는, 물질적 무질서의 논리화로 정리해 제시하여 비평가로서 유례없는 명망을 얻었다. 다른 한편 몇몇 동료들과 더불어 예술사상의 문명적 틀 자체에 의문을 제기하며 나카하라가 참조한서구 최첨단 경향의 예술 상황을 비판적으로 고찰하면서도, 도리어 서구 근대의 주체와 객체를 구분하는 이원론적 세계관 그 자체를 예리하게 비판하며 '모노하(もの派)' 의 중심축을 지탱한 존재로 평가받는 한국 태생 이우환의 활동이 있었다. ● 이리하여 나카하라 유스케도 이우환도 일본의 1970년대 이후를 언급할 때 빼놓을 수 없는 인물인 셈인데, 두 사람에게는 각각 시대 특유의 한계가 있었던 것은 부정할 수 없다. 나카하라는 자신이 주도했던 개념주의적 이론의 공격을 받고 주춤하였고, 마지막까지 '회화'와 진지하게 다시 대면할 수 없었다. 이우환도 다시 한번 회화를 서구 근대와 동일시하여 단죄한 일이 있었지만, 다행히 그의 내면의 유연한 예술가 자질 덕분에 1973년경부터 붓질의 반복으로 화면을 화가의 자유로운 움직임이나 물질의 단순한 드러냄에서 구해내는 양가적인 작품세계를 성취하는 데 성공했다. ● 나카하라의 『도쿄비엔날레 '70』에 협력했던 나는 이우환의 극단적인 반서구근대주의에 동조하기 어려웠고 다소 반감마저 느꼈으나, 본디 회화・조각에 강한 정열을 지닌 인간이었기에 이우환이 보여준 양가적 회화의 개안에는 일찍이 공감하였고 금세 그의 비평적 지지자가 되었다. 이우환의 이러한 근사한 전진에는 당시 내가 줄곧 주창한 예술 실천의 반복성이 필요하다는 견해가 다소 영향을 미쳤을지도 모르겠다. 하지만 좀더 확실한 것은 같은 시기(1970년대 초) 서울에서 이방인 이우환과 깊이 교유한 박서보의 작업방식, 즉 캔버스 바탕에 한지를 덧바르고 밑칠한 뒤 반복적인 긋기로 충돌과 간섭을 동일한 양가적 화면으로 구축해온 이른바 '묘법(描法, Ecriture)' 회화와의 동질성을 지적할 수 있다. 그 후 박서보와 이우환은 한국에서도 일본에서도 단순한 추상화가에 그치지 않은, 의미 깊은 양가적 회화의 수행자로서 중요하게 다뤄져왔다. 그들의 진가는 오늘날 한국 특유의 회화표현으로 전세계에 알려진 단색화의 집단적 양식성을 훌쩍 뛰어넘는 결과로 나타났고, 회화의 현대적 의의를 단둘이서 선도하는 돌풍을 일으켰다.

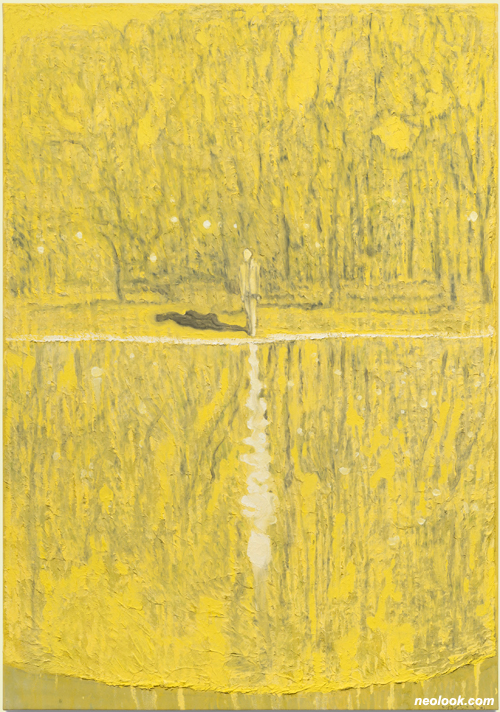

- 유근택_거울_한지에 수묵채색_150×104cm_2022

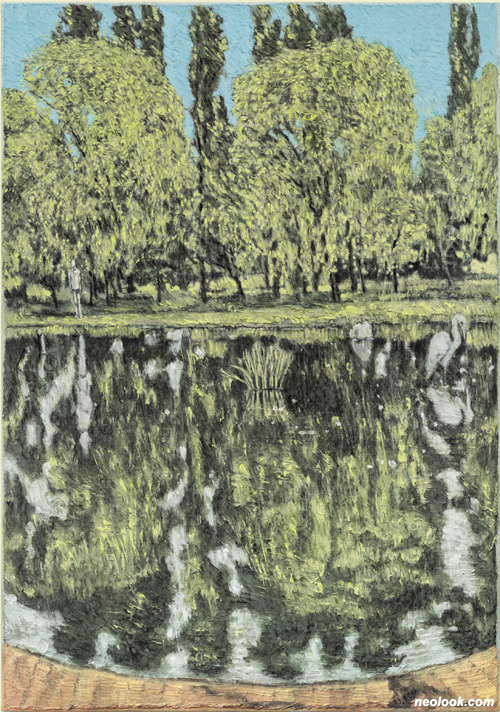

- 유근택_말하는 정원_한지에 수묵채색_146×203cm_2019

때는 1970년대였다. 미국 회화에서는 미니멀리즘의 한계를 극복해낼 만한 전망이 부재하였고 여전히 '불투명성의 회화' 등이 거론되었다. 프랑스에서는 마오주의(Maoism) 영향으로 표현과 물질의 모순을 중시하는 풍조가 강해졌는데, 회화 그 자체의 고유성을 모색하는 자세는 드물었다. 그리고 어느 지역에서든 회화는 임의로 시도된 적이 있더라도 추상의 멍에에서 벗어날 수 없었다. 일본과 한국의 현대미술도 이우환과 박서보의 귀중한 주도적 활동에도 불구하고 추상 바깥으로나아갈 수 없었다. 20세기라는 시대, 그것이 한계였을 것이다. ● 지금 생각해보면 기이한 일인데, 이런 '회화 빙하기'가 한창이던 1977년 4월 나는 잡지 『미술수첩(美術手帖)』 편집부를 설득하여 회화에 관한 특집을 마련했고, 거기에 「회화에 관한 10장(絵画に関する10章)」이라는 에세이를 기고했다. 당시 사람들은 회화가 이미 한물갔다고 생각했고 그 대신 '평면'이라고 부르는 것이 '동시대 시류'라고 여겼다. 편집부가 타협해서 특집 타이틀을 「회화의 평면과 평면의 회화(絵画の平面と平面の絵画)」라고 붙인 것은 이런 이유 때문이다. 그리고 그평면은 어떤 의미로든 추상을 뜻한다는 데에 의문의 여지가 없었다. 내가 말하는 '회화' 또한 형상이나 이미지를 전제로 할 수는 없었다. 그럼에도 불구하고 나는 기선 제압하는 태도로 '회화의 본질은 반투명성이다'라고 밀어붙였다. 좌담회는 기묘하게 쥐 죽은 듯이 조용해졌다. 『도쿄비엔날레 '70』의 성공 이후 위세가 당당했던 나카하라 유스케는 뜻밖의 화제(회화의 부활)에 의기소침한듯싶었고, 젊은 두 명의 비평가는 딴청 부리며 쓸데없는 잡담을 했다. 하지만 뜻밖에도 최대의 난적이라고 생각했던 후지에다 데루오(藤枝晃雄)가 쉬는 시간에 옆에 있던 나에게 "회화가 반투명이라니, 괜찮은 말이군요"라고 말을 건넸다. ● 늙은 평론가의 감상적인 옛날 얘기라고 여길 수도 있겠다. 하지만 회화 부재의 30년 동안 구상을 제외한 '회화'를 놓고서 이런 논의를 진행했던 것 자체는 지금 돌이켜보니 나쁘지 않았다. 왜냐하면 당시는 형상과 이미지를 결여했다고 해도, 회화의 본질을 반투명이라고 보는 논의의 근거가 조금도 낡지 않았기 때문이다. 나는 범속한 것을 좋아하는 비평가라서 예언자적 부류를 믿지 않는다. 허나, 회화의 반투명성은 바로 지금 진지하게 논의해야 할 사안이라고 생각한다. '반투명성'이라는 말로 나는 무엇을 이야기하려고 했던 것일까. 그 후 10년이 흐른 뒤 1986년 6월, 박서보의 도쿄화랑 개인전에 도록 평론글에 나는 이렇게 썼다.

- 유근택_반영_한지에 수묵채색_100×205cm_2023

- 유근택_반영_한지에 수묵채색_145×102cm_2023

- 유근택_반영_한지에 수묵채색_146×102cm_2023

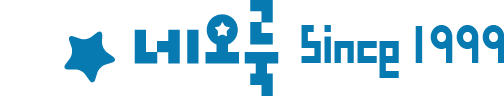

- 유근택_봄 - 세상의 시작_한지에 수묵채색_242×206cm_2023

- 유근택_봄 - 세상의 시작_한지에 수묵채색_250×206cm_2023

"뛰어난 회화는 왜 반투명인가. 마티에르(매체의 물질성)의 불투명한 벽이 드러내는 물자체의 발현을 실존적으로 긍정하는 즐거움과 그 벽의 저편에 혹은 바로 앞에 시각이 투명하게 비쳐지고, 때로는 뜻하지 않은 비전이 생기는 즐거움을 둘 다 향유하도록 해주기 때문이다. (...) 회화는 이 양극단의 어느 쪽이든 한쪽에만 치우쳐서 얻을 수 있는 것은 아무것도 없고—모노크롬 회화는 불투명성에 치우친 예이며, 삽화나 개념도 같은 그림은 투명성에 치우친 결과다—그 중간의, 반투명성의 애매함을 견뎌야만 한다. 그애매함, 벽도 풍경도 아닌, 말하자면 창(窓)이 지닌 양가성에야말로, 회화의 깊이, 예측 불허(변덕스러움), 리얼리티, 허구성, 요컨대 회화의 풍요로움의 일체가 깃들어 있다." ● 하지만 이렇게 쓴 다음에도 일본과 한국의 풍경은 그다지 달라진 것이 없었다. 애니메이션이나 게임 등 서브컬처의 성공에 가려진 회화를 점점 잊어버린 일본에서는 1960년대 이후 그래픽 디자인계의 인기 스타였던 요코오 다다노리(橫尾忠則)가 1982년 갑자기 피카소나 피카비아를 모방하며 창조적 회화를 그리는 작가가 되려고 의욕을 보였는데, 그 본령이 발휘되기까지 1988년 「다원우주론」, 나아가서는 2000년 이후의 「Y자형 골목길」 시리즈를 기다려야만 했다. 그래도 과감하게 고전미술의 성과를 끌어들여 형상과 이미지에 중요한 역할을 부여한 요코오의 회화 영역안에서의 횡단은 일본 현대미술계의 기이한 풍경이었다. 희귀종이었던 요코오를 예외로 놓고 생각해보면, 일본은 여전히 이우환의 양가적 추상회화 이상의 가치를 몰랐던 것이다. ● 이미 아셨을 것이다. 2000년 가을, 유근택의 작품과 만난 일이 내게 어느 정도로 엄청난 '사건'이었나. 이우환과 박서보에 의해서 가까스로 견지되어 온 회화의 반투명성이라는 미적 요소가, 그와 맞먹는 수준의 의미 있는 붓질과 지금까지 본 적 없는 한층 솔직한 구상 표현의 붓질로 더할 나위 없이 섬세하고 깊이 있는 성찰로서 성취된 것이다. 당시의 유근택 그림은 앞서 박서보 평론에 서 언급했듯이, 필시 "벽도 풍경도 아닌, 말하자면 창이 지닌 양가성"으로 살아 숨쉬었다. 작업실 창문을 통해 정점관측하듯이, 매일 관찰하는 숲속 오솔길과 지나가는 사람의 그림자. 일상에서 쉽게 마주치는 시시하고 밋밋한 것들은 화가와, 화가가 매일 산책길에서 관찰하는 풍경 사이의 보이지 않는 창틀에 의해 (그리고 그것을 대변하는 울타리에 의해) 이원화되며, 그 이원성이 작가와 대상세계와의 말소하기 어려운 시간의 엇갈림—산 자와 죽은 자의 엇갈림에 이르는 거리—으로서구조화되고 있음을 정감 있게 보여준다.

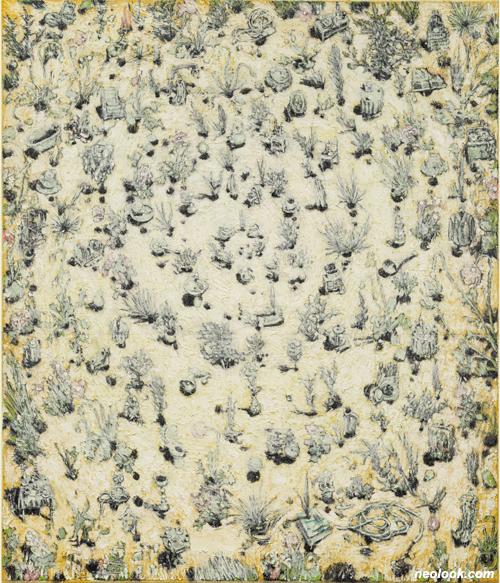

- 유근택_분수_한지에 수묵채색_258×206cm_2023

- 유근택_분수_한지에 수묵채색_258×206cm_2023

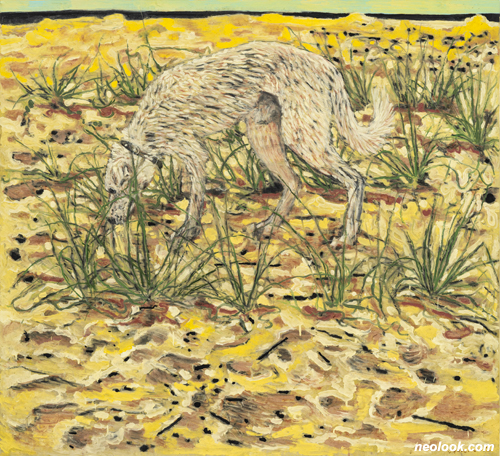

그림을 그리는 사람과 그려진 풍경 사이의 치명적이고 비극적인 거리를 의식하는 것은 이 화가의 타고난 예술적 감성에서 기인한 듯싶다. 우리는 화가가 초년생 시절에 그린 놀라운 대작 「유적-토카타(질주)」(1991)에서 그러한 거리의 인식을 이미 명확하게 회화적으로 처리했음 알고 있다. 할머니에게서 매일 들었던 한국 시민의 비극적인 역사를 주제로 다루고 있는 이 대형 작품이 드러내는 것은 결코 말해진 이야기(narrative)가 아니다. 이야기로는 결코 드러나지 않는 차원을 내포한 사건에 대한 통찰로 구성되어 회화적으로 가공된, 한 편의 창작물이자 비극이다. 이 벽화 같은 작품의 첫 부분과 끝부분이 그리스 비극에 으레 붙는 코러스를 연상시키는 무수한 사람들의 무표정한 얼굴로 메워졌고, 더욱이 고문을 연상시키는 장면에 겹친 부처의 얼굴 등, 사상(事象)의 단일성・일원성을 넘어선 핵심적인 필치가 회화 특유의 중층적 생기를 자아낸 것을 놓칠 수 없다. ● 이 작품 이후 일상생활의 관찰과 공상, 허구에서 포착해낸 다양한 주제・형상・이미지가 유근택 작업에 엄청나게 중요한 피와 살이 되었다. 그러한 작품들을 나는 비평가로서 이례적이지만 놀라움과 감동으로 받아들였다. 그림이 극적이기 때문이 아니다. 형상 묘사의 밀도가 뛰어나서 그런것도 아니다. 농밀한 동아시아적인 전통적인 수묵과 과감한 현대적 도시 풍경이 편견 없이 공존 하기 때문만도 아니다. 화면에 끌어들인 모든 요소들이 서로 녹아들 수 없는 시제(時制)를 지니며, 말하자면 내재적인 상호 비판을 전개하고 있기 때문이다. 그리는 사람과 그려진 것 사이의 불가피한 시간차를 메울만한, 그러한 붓질의 투입. 그의 회화는 결코 하나의 이야기로 끝맺은 적 없고, 끝나지 않는 세계로의 관여로 감동을 준다. 한마디로 말하자면, 유근택의 작품에서는 그림이 자기 그림을 비판하며, 그 비판의 척력(斥力)으로 화면은 잘 보인다고도, 보이지 않는다고도 할 수 없는 반투명의 중간지대로 부유하듯, 가상성을 드러내고 있다. ● 하나만 예로 작품을 다뤄보겠다. 2007년 이후 이따금 제작된 「자라는 실내」 시리즈. 사람이 사는 넓은 서양식 거실과 그 거실 바닥에서 천장까지의 공간을 다 채운 채로 부유하는 다양한 종류의 자잘한 나뭇가지. 살아있는 인간의 의지나 감정을 무시하고 끝없이 자라나는 식물의 거대한 군집과 평온한 거실 공간 사이에 기묘한 휴전 상태가 성립한다. 두 개의 공간 표상과 생명 원리가 명 료하게 이층으로 나뉘어 서로가 서로의 생존 원리를 위협하면서 어느 한쪽에게 일방적인 지배권을 내맡기지 않는다. 그림을 보는 사람은 어디에 자리 잡으면 좋은가. 어느 쪽으로 리얼리티를 느껴야 하는 것인가. 무언가 보인다는 것의 이중성, 의미를 지닌 공간의 비결정성. 우리가 살아가는 현실에 잠재된 양가적 애매함을 이토록 명확하게 제시해 보인 회화가 일찍이 있었던가. 이와 같 은 회화를 앞에 두고 우리는 일원적으로 말하는 것의 무의미함을 깨달으며 세계의 깊은 다양성과 초월성으로 이끌리는 게 아닐까.

- 유근택_자화상_한지에 수묵채색_40×29.5cm_2018

형상과 이미지를 과감하게 도입한 방식이 유근택의 작품세계를 새로운 영역으로 이끌었던 것은 분명하다. 하지만 회화의 반투명성을 고양시킨 내재적 비판은 1980년대 이후 이우환의 기상학적 회화나 1990년대 이후 박서보의 이른바 '지그재그' 회화에서 원리적으로 수행된 방식이었다. 유근택의 등장이 세대의 단절이 아닌, 좀더 뜻깊은 발전적 계승을 성취한 결과라고 한다면, 그것은 한국이나 일본이 경험할 수 있었던 멋진 역사적 쾌거가 아닐까 생각한다. ■ 미네무라 도시아키 번역 / 김정복

- 유근택_창문_한지에 수묵채색_146×101cm_2022

- 유근택_폴과 해변_한지에 수묵채색_128×140cm

Yoo Geun-Taek, or Translucency of Painting ● The first time I saw Yoo Geun-Taek's work was in the fall of 2000. I happened to visit the Museum of Contemporary Art (presently The National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea) in Gwacheon in the suburb of Seoul and saw the group exhibition Young Korean Artists 2000: Toward the New Millennium. In this show, he had some six ink paintings from the series The Long Fence (2000). I am by no means quick to judge, but at that time I immediately knew I saw a great artist. I could barely contain my excitement. Since then, I have written on his art three times, all in an openly admiring manner. Therefore, I decided to change gears this time by revealing my own critical standard and background after close to a half-century of writing art criticism in a country in proximity to Korea in order to clarify why Yoo's painting is special and precious today to me and us all. Since I will try to recall the past five decades despite my waning power of recollection, I hope the readers will forgive me should I make factual mistakes as though grains of rice spilling from a frayed bamboo basket. *** ● In 1970, when I began my career as an art critic in Japan, the vanguard critique of the ancient regime reached its apogee, with two major arguments vying for dominance. On the one hand, there was the critic Nakahara Yūsuke, who as the commissioner of Tokyo Biennale '70. He had won unprecedented acclaim by sorting out the chaotic Anti-Art tendencies that had run all through the 1960s in reference to contemporary Euro-American frontrunners, emptying emotionalism and regionalism from them, and logicalizing them as material non-orders devoid of the syntax of traditional art. On the other hand, there was the Korean-born theorist-artist Lee Ufan (born in 1936), deemed as the central figure of the "Mono-ha" (School of Things) movement, who together with a handful of like-minded artists, questioned the very framework of civilization that governed aesthetic thought, critically reevaluated the cutting-edge Euro-American practices which Nakahara referenced, and sharply critiqued the subject-object dualism that underscored Western modernism. ● Both Nakahara and Lee thus became the indispensable figures in the discussion of Japanese art after 1970. Yet, neither was free from the limitations particular to their time. Trapped by his own conceptualist logic, Nakahara could never honestly reconcile with "painting." Lee, too, once rejected painting by equating it with Western modernism. Yet, fortunately saved by the tender inner self as an artist, he managed to transform painting through repetitive brushstrokes into a "mutually responsive" realm of expression wherein the pictorial plane is liberated from both the painter's tyranny and mere material exposition. ● Having collaborated with Nakahara to realize Tokyo Biennale '70, I had difficulty sympathizing with, even feeling antagonistic to, Lee's extremist rejection of Western modernism. However, since I was passionate about painting and sculpture, I soon found myself sympathetic to his engagement with "mutually responsive painting" and in no time became his supporter. At that time, since I frequently wrote about the need for repetition in artistic practice, my idea might have somehow affected his brilliant progress. More certain, though, is the resonance between Lee's series and Park Seo-Bo's (1931–2023) painting series Ecriture. At that very same period, in the early 1970s, when Lee stayed in Seoul and Park served as his host, the latter was developing a kind of mutually responsive painting, that is, practice that embraces the mutual interference between the repeated brushstrokes and the paint covering the support. Subsequently, in both Korea and Japan, Park and Lee became proponents of mutually responsive painting, the significance of which goes beyond being a type of abstraction. The importance of their mutually responsive painting far exceeds that of Dansaekhwa as a collective style that has been afforded high international approval as the painterly expression original to Korea. It was as though Lee and Park were two solitary figures staking a claim for painting's contemporary relevance. ● During the 1970s, American painting, still concerned with such ideas as "opaque painting," lacked the intelligence necessary for overcoming the pitfalls of minimalism. French painting revealed a Maoist-inflected tendency to focus on the contradiction between expression and material, while failing to scrutinize the particularity of the medium. In any other regions, when painting was attempted, if at all, it was unable to free itself from the yoke of abstraction. In Korea and Japan, despite a precious initiative by Lee and Park, contemporary art could not step out of abstraction. It must have been an unsurmountable limitation of twentieth-century art. ● Now that I think about it, I did something peculiar in such a "severe winter" for painting: in 1977, I managed to convince the Bijutsu techō editor to run a special feature on painting in its April issue and let me contribute an essay entitled "Ten Chapters on Painting." Back then, kaiga (painting) was considered passé; instead, the appellation of heimen (literally "flat surface") was fashionable. That is why the magazine editors came up with a compromise idea for the feature title, "Flat Surface of Painting / Painting of Flat Surface." At any rate, hardly anybody doubted that this heimen was nothing but abstraction of one sort or another. In writing on "painting," I must avoid referring to forms and images. Notwithstanding, I recklessly declared: The essence of painting is translucency. The roundtable discussion for the feature was curiously quiet. At the top of his game since the successful Tokyo Biennale '70, Nakahara was almost speechless facing an improbable topic (that is, painting revival), while two younger critics shrank from the real topic, filling time by idle talk. Unexpectedly, Fujieda Teruo, whom everyone had thought to be my worst enemy, came to me during a break and murmured, "It is brilliant to say that painting is translucent." ● You may think the foregoing is an aging art critic's sentimental reminiscence, but it is not a bad thing to remember that such a discussion about "painting" took place at all without reference to figuration during the three decades when painting was in exile. That is because my argument that painting is essentially translucent has not aged a bit—except that back then, I avoided the issue of forms and images. As a critic who thinks the more ordinary, the better, I don't believe in prediction. Yet, today, at this precise moment, we should conduct a serious discussion on painting that is essentially translucent. But, what did I want to say with the term "translucency"? In June 1986, some ten years after this episode, I wrote an essay for the solo exhibition catalogue of Park Seo-Bo at Tokyo Gallery, which includes the following: "Why is a good painting translucent? Because translucency enables us to enjoy two pleasures at once. One is the pleasure of existentially accepting the luminance of the thing itself emitted by the opaque wall of matiére (materiality of the medium); the other is that of sometimes encountering an unexpected vision when our sight transparently penetrates the space beyond or before this wall. (…) Nothing may be gained should painting stick to one or the other between these two. Monochrome paintings offer merely the pleasure of opacity, while conceptually illustrative paintings afford nothing but that of transparency. Painting must endure the translucency that exists between these two opposites. In an ambiguity of being neither a wall nor a landscape, in this dualism of being a window, do all the splendors of painting reside—its profundity, fickleness, reality, and fictionality." ● Yet, since this text was published, little has changed in Japan and Korea. In Japan, where painting was further forgotten, eclipsed by the success of such subcultures as anime and gaming, Yokoo Tadanori (born in 1936), a popular graphic designer since the 1960s, suddenly decided to be a painter following the footsteps of Picasso and Picabia in 1982. Yet, we had to wait until much later to see his true achievements, as embodied by his Multiverse series in 1988 and the Y Junctions series from 2000 onward. Still, Yokoo's participation in the realm of painting which entailed his brave incorporation of traditional art and reinstatement of forms and images to their rightful place constitutes a strange sight, a rare occurrence in the contemporary art world of Japan. Aside from Yokoo, as far as I can remember, Lee Ufan's mutually responsive abstraction is the only name to speak of in Japanese painting. ● By now, the readers may understand what kind of significance my encounter with Yoo Geun-Taek's work held for me in the fall of 2000. The painterly virtue of translucency, which Lee Ufan and Park Seo-Bo managed to uphold, was achieved more delicately and more carefully by Yoo, who applied equally meaningful brushstrokes in the most frank and figurative manner that I had ever seen. Yoo's paintings I saw then pulsated in the very nature of a window that is neither a wall nor a landscape—the characteristic I have formulated above for Park Seo-Bo. ● A small path in the forest that Yoo saw every day from his studio window like a fixed-point observer. Shadows of people passing by. These mundane and insignificant setups gently announce that the invisible window frame (and the fence that stands in for it) entails the separation between the painter and the everyday phenomena he observes, and that the resulting separation is structured as an unerasable time lag between the artist and the objective world around him, which inevitably separates the living and the dead. ● His awareness of this fatal and tragic gap between he who paints a painting and that which is painted by him must be informed by his innate artistic sensitivity. We know that his awareness of this gap was already manifest in his painting in 1991, when he created an amazing mural-scale work, Remains – Toccata, Running, in his early years. It thematizes a tragic history of the Korean people that his grandmother told him day after day. However, what this huge work represents is not a narrative thus given to him. It consists of insights into the event and the dimensional gaps that can never be narrated. It is a painterly fiction, a piece of creation that is tragedy. The beginning and the end of this mural-like work are filled with emotionless faces of numerous people reminiscent of khoros accompanying Greek tragedies. Furthermore, a scene alluding to torture is covered by a Buddha's face. It is impossible to overlook his robust brushstrokes, which would transcend the event's unity or monism, exude a vivid feeling grounded in the multilayeredness typical of the medium of painting. ● Since this work, various themes, forms, and images culled from the everyday observation, as well as fantasies and fictions, became flesh and blood of Yoo's vast outputs. It is unusual for a critic like me to appreciate almost all of them with wonder and admiration. Not because his pictures are dramatic. Not because his representational skills are extraordinary. Not just because the dense East Asian painting method and the brave contemporary cityscape coexist without prejudice. But because all the different elements brought into a picture plane assume temporal tenses that will never meld with each other while undertaking an internal mutual critique, as it were. A brush is thrown in to fill an inevitable time gap between the painter and the painted. A painted painting does not culminate with a single narrative, but trembles in engagement with an interminable world. In brief, in Yoo's hand, painting critiques its own painting, with the repulsive force of critique engendering a fiction as though the picture is suspended in a hollow translucent realm that is neither visible nor invisible. ● Let me illustrate this with one work from his Growing Room series that he has time and again worked on since 2007. A large Western-style living room inhabited by some family is filled with small floating trees of diverse kinds. There exists a curious state of truce between an army of persistently growing plants and an utterly calm living space. Two sets of spatial representation and living principle exist in two layers, threatening each other's living principle without allowing one-sided domination. Those of us who see this painting wonder where to position ourselves, which reality we should take side with. The duality of seeing something, indeterminacy of space that enables signification. Has any painting more clearly presented the binary and ambiguity haunting our living reality than this one does? In front of such a painting, aren't we made aware of the futility of speaking unilaterally, being led to multiplicity and transcendence of the world? *** ● Needless to say, Yoo's courageous introduction of forms and images opened up a new horizon for the artist. Still, internalized critiques that enliven the translucency of painting have been undertaken by Lee Ufan in his meteorological painting from the 1980s onward and Park Seo-Bo in his Zigzag series from the 1990s onward. If the emergence of Yoo Geun-Taek has not simply meant a generational transition but achieved something more significant, that is, an expansion by inheritance, I then believe he has accomplished a more splendid historic feat than has ever been witnessed in Korea and Japan. ■ Minemura Toshiaki

Translated by Reiko Tomii

柳根澤、または絵画の半透明性について ● 柳根澤の絵画作品を初めて見たのは2000年秋のことであった。たまたま訪れたソウル郊外(グァ チョン)の国立現代美術館で、「韓国の若手作家たち——新千年紀を迎えて」と題するグループ展に 並べられていた6枚ほどの水墨画連作『The Long Fence』(2000)がそれであった。私は必ずしも素早 い鑑識家ではないのだが、この時だけは、大変なものを見たと即座に思い、胸の高鳴りを抑えること ができなかった。以来、この画家へのあからさまな賛辞を3度も文章にしてきた。今度書くと4回目 となる。外国在住の作家に対して、これは異例の頻度である。そこで、今回は趣向を少し変えて、半 世紀近くも韓国のすぐ近くで批評活動をつづけてきた私自身の批評の背景と基準をさらけ出しながら 、なぜ柳根澤の絵画が私(たち)にとって特別かつ貴重であったかを明らかにしてみたいと思う。記 憶の減退に逆らって半世紀を思い返すのだから、事実関係が破れた竹籠から米粒がぽろぽろとこぼれ 落ちるがごとくなのは容赦願いたい。 *** ● 私が美術批評家の道を歩み始めた1970年の日本は、旧秩序を批判・否定する前衛的気風が高揚の 極に達し、二つの議論が火花を散らす場面を現出していた。一方では東京ビエンナーレ'70の組織を 依頼された批評家の中原佑介が、1960年代から続いた錯雑たる反芸術の動向を同時代の欧米の最先 端を参照しながら脱感情化・脱地域化し、伝統芸術の語法によらない物質的無秩序の論理化として整 理して見せ、批評家としてかつてない声望を勝ち得ていた。他方、わずか数人の同志とともに芸術思 想の文明的枠組み自体を問い、中原が参照した欧米最先端の芸術状況を批判的に考察しながらも、遡 って、西欧近代の主客を弁別する二元論的世界観そのものを鋭く批判して、「もの派」の中軸を担う 存在と目されていた韓国生まれの李禹煥の姿があった。 ● かくて、中原も李も、日本の1970年以降を語る上で欠かせない顔となったのであるが、両者にはそ れぞれ時代特有の限界があったのは否定できない。中原は自身の成功した概念主義的理論に足をすく われ、最後まで「絵画」と素直に復縁することができなかった。李禹煥もまた一度は絵画を西欧近代 と同一視して断罪したことがあったけれど、幸い、彼の中の柔らかな芸術家資質によって救われ、 1973年ごろからは筆触の反復によって、画面を画家の専横からもメディウム物質のたんなる露呈か らも救い出す両義的な作品世界とすることに成功した。 ● 中原の東京ビエンナーレ'70に協働していた私は、李禹煥の極端な反西欧近代主義には同調しがた いものを感じ、反感すら抱いていたのであったが、もともと絵画や彫刻に強い情熱を抱いていた人間 であるから、李の見せた両義的絵画の開眼にはいち早く共感を覚え、たちまち彼の支持者となってい った。李のこの見事な前進には、当時私がしきりに唱えていた芸術実践の反復性の必要ということが 多少影響していたかもしれない。が、それ以上に確かなのは、全く同じころ(70年代初頭)、ソウル において客人の李禹煥と深く交わり、筆触の反復と地塗りの絵の具との相互干渉性を同一の両義的画 面の成立に向けて育てていた朴栖甫のいわゆる「描法」(Ecriture)絵画との同質性が指摘されるだろ う。その後、朴と李は、韓国においても日本においても、単なる抽象絵画にとどまらない意味深い両 義的絵画の担い手として重きをなし続けてきた。その真価は、今日韓国独特の絵画表現として国際的 に喧伝されている単色画(Dansaekhwa)の集団的様式性をはるかに凌ぎ、絵画の現代的意義をたっ た二人で高らかに掲げる風であった。 ● 時は1970年代。アメリカ絵画はミニマリズムの桎梏を克服し切るだけの見識を欠いて、まだ「不透 明性の絵画」などが云々されていた。フランスでは毛沢東主義への傾倒で表現と物質との矛盾を重視 する風潮が顕著になっていたけれど、絵画そのものの固有性を見つめる姿勢は希薄だった。そしてど の地域でも、絵画は、仮に試みられることがあっても、抽象のくびきから逃れることができないでい た。日本と韓国の現代美術も、李禹煥と朴栖甫の貴重なイニシアティヴにもかかわらず、抽象の外に 踏み出すことができないでいた。二十世紀という時代の、それが大きな限界だったのであろう。 ● 今思えば不思議なことだが、こんな「絵画氷河期」のただなかにあった1977年4月、私は雑誌『美術 手帖』の編集部を口説いて絵画に関する特集を組んでもらい、そこに「絵画に関する10章」というエッ セイを寄せた。当時、人々は絵画はもう古いと感じ、代わりに「平面」と呼ぶのが「今風」となってい た。編集部が妥協して特集のタイトルを「絵画の平面と平面の絵画」としたゆえんである。そしてそ の平面は、何らかの意味で抽象であることに疑問の余地はないとされていた。私の語る「絵画」もま た、形象やイメージを前提にすることはできなかった。だが、それにもかかわらず、私は大上段に構 えて「絵画の本質は半透明性である」とぶち上げたのである。誌上座談会は奇妙に静まり返った。東 京ビエンナーレ'70の成功以来威信を保っていた中原佑介は、不意の話題(絵画の復活)に憮然とし 、若い2人の評家は逃げ腰を浮かせて無駄話に興じ、だが、思いがけぬことに、私にとって最大の難 敵と誰もが思っていた藤枝晃雄だけは、休憩中横に並んだ私に「絵画が半透明というのはいいね」と つぶやいたものである。 ● 老いた評論家の感傷的昔話と思われようか。だが、絵画不在の30年間、具象抜きの「絵画」を相手 にこんな議論がなされたこと自体、いま思い返すのは悪くはないだろう。なぜなら、当時は形象とイ メージを欠いていたとはいえ、絵画の本質を半透明であるとした議論の論拠は少しも古びていないか らである。私は平俗を良しとする批評家であるから、予言の類を信じない。とはいえ、絵画の半透明 性は、いまこそ真面目に議論されてしかるべき事柄なのだと思う。「半透明性」という言葉で、私は 何を語ろうとしていたのだろうか。およそ10年後の1986年6月、朴栖甫の東京画廊個展に寄せて私は こう書いた。 ● すぐれた絵画はなぜ半透明なのか。マティエール(媒体の物質性)の不透明な壁が発する物自体 の輝きを実存的にうべなう(肯定する)喜びと、その壁の向こうに、あるいは手前に、視覚が透明 に突き抜けてゆき、ときには思いもかけぬヴィジョンの訪れに遭遇する喜びとを、二つながら享受 させてくれるからである。(…)絵画はこの両極端のいずれか一方にだけ偏することで得るものは 何もなく——モノクローム絵画は不透明性に偏った例であり、挿絵的概念図的な絵は透明性に偏っ た結果である——、その中間の、半透明性のあいまいさに堪えなければならない。このあいまいさ 、壁でも風景でもないいわば窓のもつ両義性のなかにこそ、絵画の深さ、気紛れ、リアリティー、 虚構性、要するに絵画の豊かさの一切がひそんでいるのである。 ● だが、こう書いた後も、日本と韓国の風景はあまり変わることがなかった。アニメやゲー ムなどサブカルチャーの成功の陰でますます絵画を忘れていった日本では、1960年代以来グラフィ ック・デザイン界の人気者であった横尾忠則が、1982年、翻然、ピカソやピカビアに倣って創造的 絵画の担い手たらんと意欲したけれど、その本領が発揮されるには1988年の「多元宇宙論」、さら には2000年以降の「Y字路」シリーズを待たなければならなかった。それでも、果敢に古典美術の成 果を取り込み、形象とイメージに重要な役割を与えた横尾の絵画参列は、日本の現代美術界の奇観で あり、貴種であった。その横尾を別にすれば、思い出す限り、日本は相変わらず李禹煥の両義的抽象 絵画以上の財産を知らなかったのである。 ● もうお分かりであろう。2000年秋、柳根澤の作品との出会いが私にとってどれほどの"事件"であっ たことか。李禹煥と朴栖甫によって辛うじて担われていた絵画の半透明性という美質が、同じように 意味深い筆触と、さらにはこれまで見たことのない率直な具象表現の筆致で、この上なく繊細にかつ 注意深く達成されていたのである。その時の柳の絵は、上掲の朴栖甫論の中で指摘したように、まさ しく「壁でも風景でもないいわば窓のもつ両義性」 で息づいていた。アトリエの窓から定点観測のように毎日見る林の中の小道と行き過ぎる人の影。こ の卑近で何気ない道具立ては、画家と画家の観察する日日の事象との間が見えない窓枠によって(そ してそれを代弁するフェンスによって)二元化していること、そしてその二元性が作者と対象世界と の抹消しがたい時間のずれ——生者と死者のずれにまで到る隔て——として構造化していることを、 優しく告げていた。 ● 絵を描く者と描かれた事象との間の致命的・悲劇的な隔ての意識は、おそらくこの画家の生得の芸 術的感性によるのであろう。この隔ての意識を、私たちは画家が大学生時代に描いた驚くべき大作 『Remains-Toccata_Running』(1991年)ですでに明確に絵画的に処方されていたことを知っている。 祖母から毎日聞かされた韓国市民の悲劇的な歴史が主題とされているが、この超大作があらわしてい るのは決して語られた物語(narrative)ではない。語りによっては決して現れない次元差を孕んだ出 来事への洞察をもって構成され、絵画的に仮構された、一編の創作物=悲劇なのである。この壁画的 作品の冒頭と末尾がギリシャ悲劇に付き物のコロスを思わせる無数の人々のほとんど無表情な顔で埋 められ、さらには、拷問を思わせる場面にかぶさるような仏陀の面など、事象の単一性・一元性を踏 み越える骨太の筆致が絵画独特の重層性による生気を放っていたことを見逃すことはできない。 ● この作品以来、日常生活の観察と空想と虚構から汲み上げられた様々な主題・形象・イメージが 柳根澤の膨大な制作の肉となり血となっていった。そのほとんどを、批評家としては異例のことだが 、私は驚きと感動をもって受け入れてきた。絵柄が劇的だったからではない。形象描写の密度が並外 れていたからでもない。濃密な東アジア的描法と果敢な現代的都市風景が偏見なしで同居しているか ら、だけでもない。画面に持ち込まれたすべての要素群が、互いに融け合うことのできない時制を帯 びて、いわば内在的な相互批判を展開しているからである。描く者と描かれたものの間の不可避的な 時間差を埋めるべき、さらなる筆の投入。描画は決して一つの語りで終息することはなく、終わるこ とのない世界との関与で打ち震えている。一言でいえば、柳根澤の作品では絵がおのれの絵を批判し 、その批判の斥力で、画面はよく見えるとも見えないとも言えない半透明の中空域に浮くがごとき仮 想性を現じているのである。 ● 一つだけ例示的作品を取り上げよう。2007年以降たびたび制作された「Growing Room」のシリー ズ。人の住む大きな洋風居間と、その居間の床から天井までの空間を埋め尽くして浮遊するさまざま な種類の小樹木。住んでいるはずの人間の意志や感情を無視して、ひたすら成長してやまない植物の 大軍団と平静そのものの居室空間との間に奇妙な休戦状態が成立している。二つの空間表象と生命原 理がくっきりと二層をなして、互いが互いの生存原理を脅かしつつ、一方的な支配権をゆだねていな い。絵を見る者はどこに定位すればいいのか。どちらにリアリティーを感ずるべきなのか。何かが見 えることの二重性、意味をもたらす空間の非決定性。私たちの生きる現実にひそむ両義的あいまいさ をこれほど明確に提示し切った絵画がかつてあっただろうか。このような絵画を前にして、私たちは 一元的に語ることの無意味さを思い知らされ、世界の深い多義性と超越性に導かれるのではあるまい か。 *** ● 形象とイメージの果断な導入が柳の新生面を開いたことは言うまでもない。けれど、絵画の半透明 性を生気づける内在的批判ということは、李禹煥の1980年代以降の気象学的絵画や朴栖甫の90年代 以降のいわゆる「ジグザグ」絵画において原理的に遂行されていたことであった。柳根澤の登場が、 世代の断絶をではなくもっと意義深い発展的継承をこそ成し遂げたのだとすれば、それは韓国や日本 が経験しえた素晴らしい歴史的快挙なのではないかと思う。 (2023年9月28日) ■ 峯村敏明

Vol.20231025f | 유근택展 / YOOGEUNTAEK / 柳根澤 / painting.installation