- ● homepage

- ● archives

- ● restoration

- ● books

- ● big banners

- ● post board

- ■ neo's search

- ■ about us

- ■ 게재방법 안내

- 개인정보처리방침

- [email protected]

- Tel. 02_335_7922

- Fax. 02_335_7929

- 10:00am~04:30pm

- 월요일~금요일

- 3/3(월) 대체공휴일

요괴생활(A Bizarre life)

최모민展 / CHOIMOMIN / 崔모민 / painting.drawing 2021_0914 ▶ 2021_1015 / 월,공휴일 휴관

● 위 이미지를 클릭하면 네오룩 아카이브 Vol.20190910f | 최모민展으로 갑니다.

별도의 초대일시가 없습니다.

기획 / 임진호 후원 / 서울시립미술관

본 전시는 서울시립미술관에서 진행하는 2021 신진미술인 전시지원 프로그램 선정으로 진행되었습니다.

관람시간 / 12:00pm~06:00pm / 월,공휴일 휴관

아웃사이트 out_sight 서울 종로구 창경궁로35가길 12 GF (혜화동 71-17번지) Tel. +82.(0)2.742.3512 www.out-sight.net

작가와의 대화는 보통 풍경에 대한 이야기에서 시작되었다. 일하고 그림 그리는 자기 자리에서 보이는 풍경, 집으로 가는 길, 홍제천 주변, 한 사람의 또는 한 세대의 주어진 자리로서 기호화되는 장소들, 그리고 늘 그곳에 있지만 빛에 따라, 계절에 따라, 노후화와 철거와 개발과 인간 세상의 풍파에 따라 조금씩 모습을 바꾸는 풍경에 대해. 그가 도시에 있을 때나 어느 시골의 작업실에서 그림을 그릴 때에도, 풍경은 늘 바로 그릴 수 있는 대상으로 거기 있었을 것이다. 그러나 풍경은 순진한 객체인 채 눈앞에 놓여 있는 것만은 아니다. 사람들이 머무르다 떠나고, 사람들이 사고팔고, 사람들을 울고 웃게 만드는 대지와 거리와 아파트와 건물들은 살아서 뚜벅뚜벅 움직이지 않음에도 불구하고 사람들을 삼키고 뱉고 고갈시키며 빠르게 몸집을 불려 나간다. ● 풍경이 변화하는 맹렬한 속도는 그에 비해 너무나도 미미한 자신의 나아감에 무력함을 선사한다. 고향 집이라 부를 수 있을 아파트가 있던 자리에는 주상복합단지가 그 눈부신 파란 유리창 위로 향수를 튕겨낸다. 도시는 아무것도 쥐지 않고 태어난 이들을 그 풍경 바깥으로 열심히 뱉어낸다. 열심히 살면 나의 자리를 마련할 수 있을 것이란 보편적 확신은 사라지고 시키는 대로 따르는 것만으로는 그저 서서히 침몰해갈 뿐이라는 것을 알아버렸다. 그리고 여기저기서 떠들어대는 일확천금과 인생역전의 새로운 신화들이 또 다른 절박한 그림자를 드리운다. 그런 풍경 속에서 묵묵히 자기 자리를 지키며 산다는 것은 쉽지 않은 일이다. 숨 쉴 자리 하나 마련하는 것 자체가 별일이 되어 버렸다. 하물며 예술을 하며 산다는 것이란. 그림을 그리며 살아가는 것은 종종 그리는 삶과 생존하는 삶의 지독한 분열을 강요한다 (예술의 언저리에서 글을 쓰며 사는 것 또한 마찬가지다). 그래서인지 예술인의 삶은 마치 유령 사과¹처럼 속이 텅 빈 껍데기인 채로 끝없이 확장해가는 도시 위에 매달려 있곤 한다.

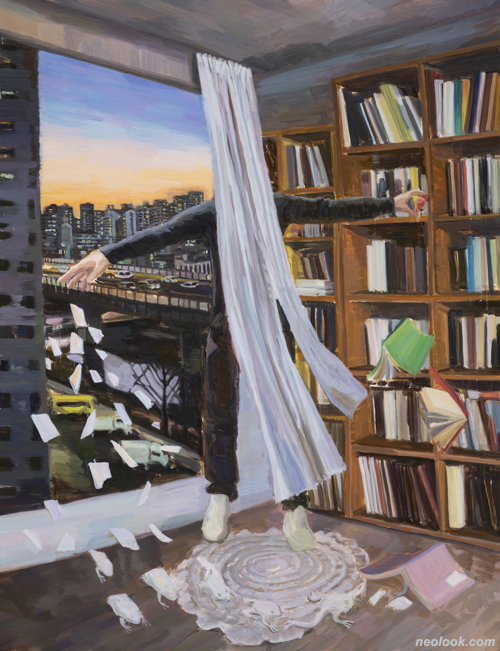

- 최모민_숲 그리기:환영_캔버스에 유채_195×150cm_2021

- 최모민_종이꽃_캔버스에 유채_195×150cm_2021

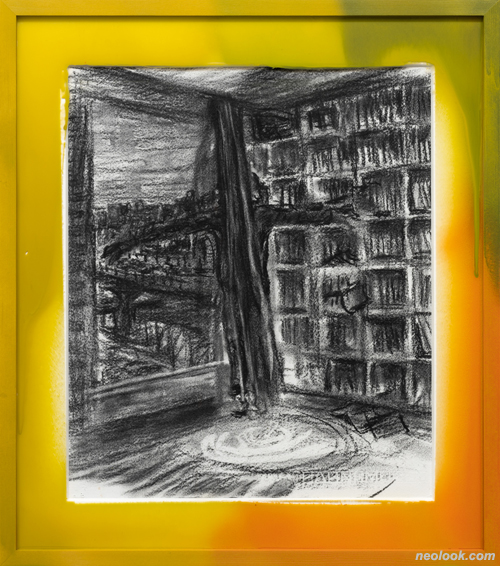

- 최모민_거실에서 드로잉_혼합매체_44×50cm_2021

최모민이 그리는 그림에서는 그러한 분열의 조짐들이 풍경을 점유한다. 다중적 시공간으로의 벌어진 틈으로, 그리고 여러 자아들로의 흩어짐으로. 머리를 감싸고 서성거리는 인물들의 풍경에서는 불안의 정서가 감지된다. 그러나 그것은 어디에서 적을 맞닥뜨릴지 모르는 팽팽한 긴장감에서 야기되는 불안이라기보다는, 서서히 삶을 분열시키지만 실재하지 않는 적의 형상을 한없이 기다려야만 하는 불안의 기시감에 가까울 것이다. 거기엔 날카로운 이빨을 드러낸 천적이 아닌 끝없는 다원성의 세계로 흩어져 버린 공정과 정의의 공허함이 있다. 실체가 없는 적 앞에서 낼 수 있는 용기라는 것은 망상에 가까운 것이다. 오늘의 젊은이들은 이생망이라는 염불을 외며, 살아있지만 기댈 수 있는 삶의 이유를 상실한 채, 존재하지만 존재하지 않는 삶을 나름의 방식으로 견뎌낼 뿐이다. 최모민이 지난 한해의 전시들에서 보여주었던 것들은 이와 같이 극단적 무기력에 짓눌린 인물과 도시의 풍경이었다. 벽과 계단과 난간에 늘어져 붙은 인물들 (「계단에 사람들」), 나뭇가지에 위태롭게 매달려 먼발치의 아파트 단지를 내려다 보는 사람 (「매달리다 연작 6」), 거미줄에 포획된 사람 (「매달리다 연작 7」, 벌거벗으며 늪으로 향하는 사람들 (「늪에서 연작」). 그러나 매달리고 걸려있고 늪을 바라보는 사람들에게서, 문득 도약하고 버티고 응시하는 듯한 모호한 반전의 틈을 감지할 수 있었다.

- 최모민_불꽃놀이_캔버스에 유채_117×91cm_2021

- 최모민_불꽃놀이 드로잉_종이에 목탄_ 42×30cm_2021

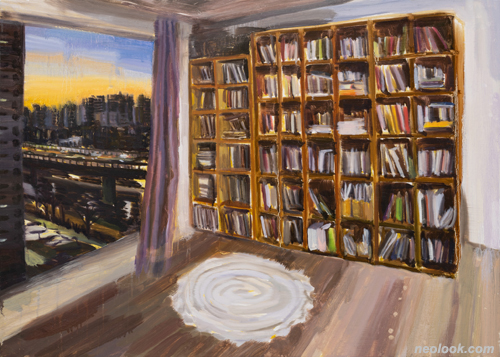

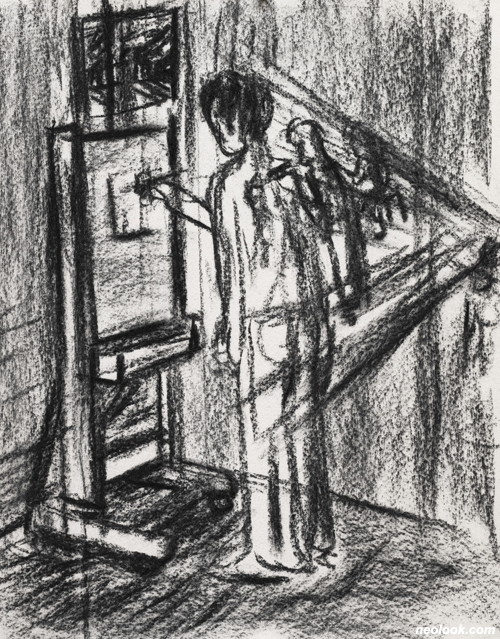

이번 전시에 등장하는 최모민의 ‘요괴들'에게는 무력한 태도 위로 분열의 징조가 더욱 선명하게 드리운다. 작가는 얼음으로 덮인 풍경 속에 얼음의 빛과 질감으로 자기 이미지를 그려넣었다 (「얼음사람 만들기: 분신」, 「얼음사람」). 머리를 감싸다가, 고개를 젖히다가, 손을 들어올리다가 순간 얼음으로 굳어버린 형상이다. 얼어붙은 (어쩌면 얼음으로 위장한) 인물들은 풍경 속으로 자연스럽게 스며든다. 작가는 그저 저기 보이는 풍경의 한 조각인 듯 차가운 거리를 두고 자신의 이미지를 다루었다. 마치 실체 없이 남겨진 얼음 껍데기처럼, 작가는 그려진 자기를 얼음 풍경 속에 덩그러니 남겨두었다. 이젤 앞에 서서 그림을 그리는 자기 위로 그림을 그리는 자기를 그리고 또 그리는 「자기 착취하는 남자: 작업실에서」, 또 꽁꽁 얼어붙은 작업실 안에서 그림을 그리는 자기를 그린 「녹는 손」 에서는 분열된 작가의 시선이 다시 그 자신과 그가 처한 상황을 응시하기를 반복하는 자기지시적 풍경을 재현한다. 분열될수록 선명하게 드러나는 자신의 모습을 그려내는 일만큼 기이한 일이 어디에 있을까? 흩뿌려지는 현실 속에서 더욱 신실하게 존재하는 자신의 삶이야말로 요괴의 그것이 아니던가? ● 책이 빼곡하게 꽂힌 책장 옆으로 고가도로를 향해 난 창문이 그림처럼 걸려있다. 창문으로 들어온 바람에 커튼이 거세게 휘날린다. 머리를 괴고 누운 사람 머리 위로 바람이 지나간다 (「웃는 남자」). 커튼이 가만히 흔들린다. 누워있던 사람이 있던 자리가 텅 비었다 (「거실에서」). 커튼 뒤에서 두 팔이 뻗어 나왔다 (「종이꽃」). 커튼 뒤에 숨어 두 팔을 뻗은 사람을 그린 흑백의 드로잉이 있다 (「거실에서 드로잉」). 커튼을 흔드는 바람은 창 밖에서 방 안으로, 방 안에서 프레임 밖으로, 사람이 없는 방 안으로, 사람이 있는 목탄 드로잉으로 불어든다. 안과 밖의 풍경이 끊어질듯 이어지며 각기 다른 벽에 걸려있는 네 개의 그림을 넘나든다. 그림이 조금씩 내부와 외부의 한계선, 캔버스의 프레임을 뚫고 나와 이곳의 현실을 향해 열리는 것을 보며, 공허와 무력함 속에 분열되어가던 작가의 시선이 조금씩 그 바깥 어딘가를 향하고 있음을 조심스럽게 추측해본다. 지금 바로 우리 눈 앞에서 폭죽이 터지고 있다 (「불꽃놀이」). 「종이꽃」의 커튼 뒤에 벌려진 두팔은 내부에서 외부를 향해 스스로의 존재를 확인하는 증거와도 같이 작동한다. 그 손을 떠나 바람에 흩날리는 종이조각들은 개구리로 변신한다. 장난같은 마법이지만 거기에는 분명 삶을 향한 나지막한 의지가 담겨있을 터이다. 장난은 현실의 육중한 공허함을 깃털처럼 날려버리는 진정한 생존의 마법이기 때문이다.

- 최모민_자기 착취하는 남자: 작업실에서_캔버스에 유채_195×150cm_2021

- 최모민_자기 착취하는 남자 드로잉_종이에 목탄_32×25cm_2021

극단적 절망 속에서 공포와 호기심이 공존하는 새로운 존재 양태를 탐색하듯 최모민의 그림은 끊임없이 그가 포착한 풍경의 다중성을 갱신한다. 생각해본다면 분명 요괴의 삶은 분열된 현실에서 비롯되지만, 그 본질은 비현실이라는 점에서 꿈속의 삶과도 다를 바 없다. 그러므로 오늘날의 요괴는 장자의 나비가 되어 날아갈 수도 있는 것이다. 그래서 어쩌면 최모민의 얼음은 유령처럼 실체없이 존재하는 껍데기(구식 인간)의 삶이 아닌, 보호색으로 자신을 숨긴 채 낯선 풍경 속을 살아갈 준비를 하는 새로운 요괴의 번데기일지도 모른다. ■ 임진호

¹ 내리는 비가 그대로 얼어붙을 정도로 추운 날에는, 사과나무 가지에 속이 빈 얼음사과가 열린다. 사과 표면의 얼음이 온실처럼 내부의 온도를 높이면 사과는 흘러내려 버리고 사과 모양의 얼음이 그 자리를 대신한다고 한다. 마치 실체는 사라지고 껍데기만 남은 유령처럼.

- 최모민_거실에서 드로잉_혼합매체_50×44cm_2021

A Bizarre Life ● The conversations with the artist usually began with landscapes. About the view from his place where he works and paints, the way home, around Hongjecheon, about the places that are symbolized as given places for a person or a generation, and about the landscape that is always there but subtly changes according to the light, the season, deterioration, demolition, development and the turmoil in the human world. Whether he was in a city, or painting in a studio in the countryside, the landscape would have always been there as an object ready to be painted. But the landscape is not just placed before one's eyes as an innocent object. Though the sites and streets and apartments and buildings do not walk around alive; they swallow, spit, and exhaust people, quickly increasing the size of their bodies, as they are occupied and left, bought and sold, making people laugh and cry. ● The fierce speed at which the landscape changes contrasts with the insignificant progress that one makes, leaving one with a sense of helplessness. Where there used to be an apartment which one might call one's hometown, a newly built mixed-use complex now flicks off any sense of nostalgia with its gleaming glass window. The city eagerly spits those who have been born with nothing in their hands out of that landscape. The universal confidence that one can find a place for oneself if one works hard has died out. People have realized that doing what they are told will only have them slowly sinking. And the new legends of rags to riches that people go on about cast another desperate shadow. It is in no way easy to steadily keep one's place in such a landscape. It has become a big deal even to find a place for one to breathe. And to make a living as an artist on top of that. Living as a painter often requires a serious fragmentation in the painting life and surviving life (the same goes for living as a writer near the boundary of art). And that may be why the life of an artist often hangs above an endlessly expanding city as if it is an empty shell, similar to a ghost apple.¹ ● Such signs of fragmentation occupy the landscape in Choi's paintings, through the gap to multiple spacetimes, and the dispersion of multiple egos. One can sense the feeling of anxiety in the sight of figures that pace around, with their heads in their hands. However, this feeling is not so much the anxiety from the tension caused by the fact that one may encounter an enemy anywhere, but the sense of anxiety's déjà vu, having to wait endlessly for the figure of the enemy which does not exist in reality yet gradually breaks life apart. There exists not the enemy that shows its pointed teeth, but the void left by the fairness and justice that have scattered into the world of endless diversity. The courage that one can show standing before an enemy of no real existence is more like a delusion. The young today repeat the chant, ‘i-saeng-mang' (I'm done for in this lifetime), alive but without a reason to live for, in their own way enduring a life that exists but doesn't exist. What Choi presented in his exhibitions in the past year was the sight of such people and the city weighed down by extreme lethargy. People drooping, stuck to the wall, stairs and handrails (「People on stairs」), a person looking down on an apartment block afar, precariously hanging on a tree branch (「Hang on series 6」), a person caught in a spiderweb (「 Hang on series 7」, people heading towards a swamp as they are taking off their clothes 「In the swamp」. But from the people clinging, hanging and looking towards the swamp, one could sense a vague chance for a twist in how the people seemed to be leaping, enduring and staring. ● For Choi's ‘bizarre creatures' that appear in this exhibition, the signs of fragmentation cast even clearer. The artist has painted an image of himself on the ice-covered landscape in the light and texture of ice (「Making of ice people : alter ego」, 「The ice man」). A figure is frozen while wrapping his head with his hands, another while throwing back his head, and another while lifting his hands. The figures that are frozen (or perhaps disguised as ice) blend naturally into the landscape. The artist treated his image with cold distance, as if it was only a piece of the landscape over there. Like an ice shell left without real existence, the artist just left his painted self alone in the midst of the icy landscape. A 「Self-exploiting man: In the studio」 who stands before an easel, painting himself painting again and again on top of the painting of himself painting, and 「Melting hand」, which shows him painting in a frozen studio, depicts the self-referential scene of the artist's fragmented gaze repeating his observation of himself and his situation. Could there be anything stranger than painting the image of oneself revealing itself more clearly with greater fragmentation? Isn't the life of oneself existing ever more faithfully in the scattering reality just like the life of a bizarre creature? ● Beside the bookcase filled with books, the window facing the overpass hangs like a painting. The curtain flaps violently as the wind blows in through the window. The wind blows past the man who lies, resting his head on his hand (A smiling man」). The curtain gently sways in the wind. The place where the man used to lie is empty (「In the living room」). Two arms stretch from behind the curtain (「Paper pollen」). There is a black-and-white drawing of the person who is stretching his arms, hidden behind the curtain (「In the living room(drawing)」). The wind that sways the curtain blows from out the window into the room, from the room to out of the frame, to the room where there is no one, then to the charcoal drawing where the person stands. The scenes of the inside and the outside seem to end yet continue each other and hover between the four paintings, each hanging on different walls. Seeing the painting gradually break out of the canvas frame, the inner and outer boundaries, and opening toward the reality here, I make a careful conjecture that the artist's gaze, which had been becoming fragmented in emptiness and helplessness, is slowly turning towards someplace beyond that. See the fireworks going off in the sky right before our eyes (「Fireworks」). The arms stretched behind the curtains in 「Paper pollen」 acts as an evidence for confirming one's existence from the inside to the outside. Leaving those hands, the pieces of paper that flutter in the wind transform into frogs. It is a magic that is more like a joke, but within it would certainly exist a faint will towards life. That is because jokes are the true magic for survival that makes the heavy emptiness of reality drift away like a feather. ● As if to search for a new mode of existence where fear and curiosity coexist in the midst of extreme despair, Choi's paintings constantly renew the multiplicity of the landscapes he captures. To think about it, the bizarre creature undoubtedly stems from the fragmented reality, but it is no different from the life in dreams in that their essence is unreality. Thus the present-day bizarre creature can become Zhuangzi's butterfly and fly away. Therefore, perhaps Choi's ice is not a hollow shell (or old-fashioned mode of being), existing like a ghost without real existence, but the pupa of a new bizarre creature, hiding itself with protective coloring in preparation for living on in an unfamiliar landscape. ■ Jinho Lim

¹ On days where the weather is so cold that the rain freezes as it falls, hollow ice apples are spotted on apple trees. As the ice on the surface of an apple acts as a greenhouse, increasing the temperature on the inside, the apple, defrosted and rotten before the ice, slides out, leaving the apple-shaped ice on its place. The ice shell without real existence is left like a ghost.

Vol.20210911h | 최모민展 / CHOIMOMIN / 崔모민 / painting.drawing