- ● homepage

- ● archives

- ● restoration

- ● books

- ● big banners

- ● post board

- ■ neo's search

- ■ about us

- ■ 게재방법 안내

- 개인정보처리방침

- [email protected]

- Tel. 02_335_7922

- Fax. 02_335_7929

- 10:00am~04:30pm

- 월요일~금요일

- 3/3(월) 대체공휴일

WIND

이정진 사진집 출간 기념회 초대일시_2010_0204_목요일_04:00pm

- PHOTOGRAPHS_ 이정진 || 판형_10×11"(25.4×27.9cm) || 면수_112 pages || 발행일_November 2009 ISBN 978-1-59711-128-7 || $45.00; £30.00 || aperture foundation 45 duotone images || Hardcover with jacket

초대일시_2010_0204_목요일_04:00pm

무이무이_muimui 서울 강남구 신사동 653-4번지 레스토랑 2층 Tel. +82.2.515.3981

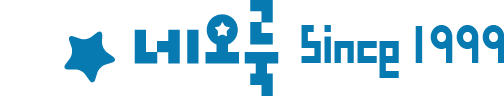

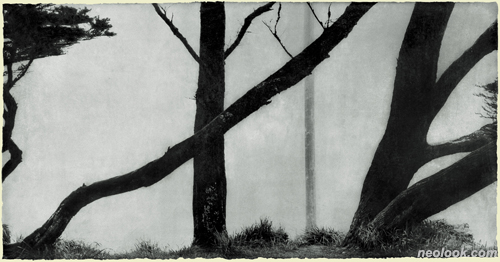

바람 (2009년, 아퍼추어 출판사)은 널리 전시되고 국제적으로 명성을 얻은 한국 사진가 이정진에 의한 새로운 작업을 보여준다. 노동적이며 질감이 돋보이는 사진작업과정으로 알려진 이정진은 수제 한지 표면 위에 리퀴드라이트라 불리우는 액체 유제를 바른다. 종이의 질감과 붓질의 흔적은 독특하게 페인트 된 효과를 불러오고, 이 질감은 이정진의 첫번째 모노그래프인 금번 책을 통해 아름답게 재생되었다. 그녀는 어린 시절 동양화와 서예를 숙지하였는데 그 예술 형태 또한 금번 작업을 통해 공명되고 있다. 바람은 모험적인 영혼을 보여주고, 그러나 쉽게 진입할 수 없는 파노라마 속의 바람이 휩 쓴 자리와 불길한 듯 예사롭지 않은 구름들에 의해 주도되는 풍경사진 시리즈로서, 이름에서 볼 수 있듯 무형의 질을 잡아낸다. 황량하게 버려진 학교버스와 하늘로 뚫려버린 천정을 가진 폐허, 바람에 날리는 기도 깃발 등 인간이 만든 것들이 강렬하고 보이지 않는 요소들 속에 재차 조명된다. 내면적 존재에 대한 은유와 이를 형성하는 힘이 이정진의 바람 속 풍경에는 한 눈에 보기에도 강렬하고 평온한 원초적인 광활함이 스며들어있다. 그 속에는 삶을 지탱하는 근본적 氣로서의 바람에 대한 불교사상의 영적 측면도 뿌리를 두고 있다. 바로 이러한 氣는 한국과 미국 남서부 등에서 만들어진 이정진의 아름다운 사진들 속에서 경험될 수 있다. 그녀는 자연세계를 사진으로 담지만 정작 그녀의 이미지는 영묘하며 꿈과 같다. ● 이정진(1961년생, 대한민국 서울출생)은 서울의 홍익대학교에서 공예를 공부하였고 이후 뉴욕대에서 사진석사를 취득하였다. 그의 사진은 미국, 유럽, 한국의 갤러리와 박물관에서 폭넓게 전시되어 왔다. 그녀의 작품은 뉴욕의 메트로폴리탄 뮤지엄, 휘트니 뮤지엄, 로스앤젤리스 카운티 뮤지엄, 휴스턴 파인아트 뮤지엄, 산타페의 뉴멕시코 뮤지엄, 과천의 국립현대예술 박물관, 부산 고은 사진관과, 경주 선재 미술관 등 한국의 유수 기관에 소장되어있다. 아퍼추어 ● 뉴욕 첼시 예술지역에 위치하고 있는 아퍼추어는 세계적으로 잘 알려진 비영리 출판사이자 전시공간으로 모든 형태의 사진예술을 홍보하는 데에 헌신한다. 1952년 사진가 안셀 아담스, 도로시아 랭, 바바라 모건, 마이너 화이트, 역사학자 버몬트 뉴홀, 작가이자 큐레이터인 낸시 뉴홀 등에 의해 창립되었다. 예지력있는 눈을 가진 이들은 아퍼추어 매거진이라는 계간지를 만들었고 이를 통해 사진이란 매체 및 사진전문인들의 발전과 홍보를 도모하였다. 1960년대 들어 아퍼추어는 책 출간으로 영역을 넓혔는데 (현재까지 500권이상이 출간되었다) 이는 사진 및 예술 역사에 있어 가장 괄목할만하며 혁신적인 것으로 평가받고 있다. 현재 아퍼추어 프로그램에는 작가 강의와 패널 토론, 한정 사진 판매, 및 미국 및 국제적인 주요 박물관과 예술 단체의 순회전시들을 포함하고 있다.

- 이정진_wind 04-55

Wind (Aperture, November 2009) showcases the newest work by the widely exhibited and internationally acclaimed Korean photographer Jungjin Lee. Known for her laborious, textural photographic process, Lee brushes liquid emulsion ("liquid light") onto the surface of handmade Korean paper (mulberry paper). The texture of the paper and the gestural marks of the brush stroke create a unique painterly effect, which is beautifully reproduced in this, Lee's first trade monograph. As a child, Lee mastered oriental painting and calligraphy, and this art form resonates throughout this work. Wind captures the ethereal quality of its namesake in a series of landscapes dominated by windswept expanses and foreboding cloud formations—panoramas that reveal an adventurous spirit, yet resist casual entry. Man-made objects, such as a dilapidated school bus, an old ruin whose ceiling is open to the sky, or wind-blown prayer flags, frequently appear marked by powerful, invisible elements. Metaphors for an internal state of being and the forces that shape it, Lee's Wind landscapes are imbued with an elemental vastness, at once powerful and serene. The work also bears a spiritual element that stems from the Buddhist belief that wind is one of the essential energies that sustains life. This energy can be felt in these beautiful photographs, which were made in Korea and the American Southwest, among other places. Lee photographs the natural world, but her images are ethereal and dreamlike. ● JUNGJIN LEE (born in 1961, raised in Seoul, Korea) studied ceramics at Hong-Ik University in Seoul and later earned a master of arts in photography from New York University. Her photographs have been exhibited extensively in galleries and museums throughout the United States, Europe, and Korea. Lee's work is included in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Whitney Museum of American Art, both in New York; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; New Mexico Museum of Art, Santa Fe; and various prestigious institutions in Korea; National Museum of Contemporary Art, Kwachon; Goeun Museum of Photography, Pusan; Sonje Museum of Contemporary Art, Kyongju. ● Aperture—located in New York's Chelsea art district—is a world-renowned non-profit publisher and exhibition space dedicated to promoting photography in all its forms. Aperture was founded in 1952 by photographers Ansel Adams, Dorothea Lange, Barbara Morgan, and Minor White; historian Beaumont Newhall; and writer/curator Nancy Newhall, among others. These visionaries created a new quarterly periodical, Aperture magazine, to foster both the development and the appreciation of the photographic medium and its practitioners. In the 1960s, Aperture expanded to include the publication of books (over five hundred to date) that comprise one of the most comprehensive and innovative libraries in the history of photography and art. Aperture's programs now include artist lectures and panel discussions, limited-edition photographs, and traveling exhibitions that show at major museums and arts institutions in the U.S. and internationally. ■

Contact: Andrea Smith, Director of Communications,(212)946-7111, [email protected]

- 이정진_wind 04-54

"영혼으로부터의 속기록" ● 풍경은 실제로 우리에게 말을 하지는 않으나, 환경은 우리의 존재, 번영, 문화적 정체성에 너무나 필수적이어서 그것이 마치 "개인 사항: 즉시 개봉 요망"이라고 표시된 메시지를 보내는 듯이 우리는 그것에 대응한다. 땅이 노래하는 것일까? 대양에서 오는 찬송가, 산에서 오는 찬가, 사랑의 노래, 송가, 만가... 등이 논리 너머에 있는 목소리로, 그러나 뼈 속에 들리는 그런 소리로 들려오는 것일까? 들리는 것은 우리 자신인데, 항상 우리 옆에 있으면서 달라붙을 구체적 대상을 찾는, 쾌락과 고뇌의 말없는 파도를 증폭시키는 공명판으로 사람이 사는 또는 살지 않는 땅을 이용하는 것일까? ● 지어진, 지어지지 않은, 남용된 또는 남용되지 않은 풍경이 그 침묵의 노래로 우리를 움직일 수 있다면, 그런 영상은 마음의 깊은 곳으로 찾아오는 강력한 대리자 같은 것이다. 한국에서 태어난 이정진은 관광 안내문에는 나타나는 일이 없는 곳에서 사진을 찍는다. 그녀의 반응은 - 튕겨진 바이올린의 현처럼 도도하고 구슬프고 울리면서 - 말로는 표현할 수 없는 땅과 과거 삶의 흔적, 공허와 자연의 힘을 무의식현상에 가까운 풍경으로 전환시킨다. 이들은 하나의 마음, 즉 그녀 마음의 탐색을 말한다. 작가의 말에서, 그녀는 "WIND 시리즈(2004)의 영상은 나의 내성적 상태와 생각을 나타낸다."고 말한 일이 있다. ● 이정진은 독학으로 사진을 배웠다. 대학을 졸업한 후 1년 동안 잡지사에 일하면서 사진을 찍었고, 그후 2년 동안은 프리랜서로 활동하였다. 좋은 경험이었지만 포토저널리즘이 자기가 갈 길이 아니라는 확신을 얻었다고 말한다. 3년째 되던 해의 대부분은 완전한 고립지역에서 살고 있던 어느 노인을 촬영하였다. 그는 산속에서 야생인삼을 찾아 다니는 일을 하고 있었는데, 사람의 삶과 자연이 조화를 이루어 간다는 어려운 과제에 근접하였다는 사실이 이정진을 매료시켰다. 매체의 요청이 아닌 자신이 만들어낸 이 이야기는 책으로 출간되었고 전시되었으며 사료로써 쓰이게 되었는데, 이는 한국에서 더 이상 아무도 야생 인삼을 캐지 않게 되었기 때문이다. 사진의 역사는 이와 같이 도전하지 않았다면 수장되었을, 구출된 이야기들로 가득하다. ● 얼마 후 1988년 이정진은 미국으로 옮겼다. 그곳 분위기는 고양된 활력과 자유로 가득한 듯 하였다. "이곳에는 예술가로서 무언가 발견할 것이 있다." New York 대학교에서 사진학 MA공부를 하는 동안, 아시아에서는 감정 표현을 더 강조하는데 반해, 이곳 학생들은 아이디어에 더 관심이 많다는 것을 깨닫게 되었다. 당시 그녀는 거리의 사진가였다. "New York시는 위대한 학교"라고 그녀는 말한다. 주제는 사람들이었지만, 그 때에도 자기자신 속의 무언가를 찾고 있었으며, 남의 사진을 찍는 것은 "훔치는 것" 같은 느낌이 들었다. 2년째 되던 해, 남서부로 여행하였는데 그곳에서 만난 사막에서 자신에 속한 영혼을 발견하게 된다. 펼쳐진 풍경이 마침내 그녀의 감성과 내재된 자아로의 통로를 보여준 것이다. ● 우리는 시각적 영상을, 이성이 언어로 해독해내기 전에, 정서적으로 경험한다. 이정진의 사진들은 이것을 고집한다. 두 방향으로 갈라지는 지점에서 평범한 도로, 자갈길, 두 개의 벽난로, 그리고 흔들리는 몇 개의 흰 선이 있는 그녀의 사진은, 의미는 고사하고 위치, 패턴, 또는 결 등으로 쉽게 설명할 수 없다. 마치 그녀가 "시는 의미하는 것이 아니라 존재해야 한다"고 한 Archibald MacLeish의 "시 예술"이라는 시를 염두에 둔 듯하다. 이정진의 어떤 사진들은 아무것도 아닌 것, 별것 아닌 것, 멈추어 바라볼 가치가 없는 것들을 그리고 있지만, 심장처럼 뛰고 있다. ● 그녀의 영상은 종종 꿈의 변두리에서 겨우 건져낸 것 같이 보이며, 렌즈나 육안으로 세밀히 본다 해도 자연이 흔쾌히 포기하지 않을 것 같은, 가려진 비밀을 뚫어보는 듯한 인상을 준다. 불명확성, 모호성, 자연의 변천하는 힘을 조준하면서, 이정진은 악천후 속에서 눈, 안개, 바람과 벗한다. 어떤 영상에서는 땅과 하늘이 그들의 수평선에서 벗어나 잘 분간하기 어려워진다, 즉 선이 뭉개진 곳에서 회색은 회색과 섞이며, 사물의 통일성은 일상 속에서는 흔히 분열로 간주되는 것마저 다스린다. 그녀의 렌즈 앞에서 하늘, 구름, 바다는 추상으로 용해되어 우리가 한때 안다고 생각하였던 자연의 단편들을 수수께끼로 만든다. ● 어떤 카메라든지 그 주어진 조건의 하나는, 그것이 보이는 것의 단편을 잘라내야 한다는 것이다. 그 부분이 아주 작은 경우 식별할 수 없게 되는 경향이 있다. 사진이 20세기 초 영화가 만들어낸 클로즈업의 모범 - 확대는 하되 정체성은 파괴하지는 않는 – 을 따르는 데에는 그리 긴 시간이 걸리지 않았다. 어떤 의미에서는 회화에서 새롭게 떠오른 정체성의 추상적 말소와 연합한 것이다. ● 카메라의 극도의 close-up 또는 거의 모든 것의 단편은 - 전자현미경의 영상으로부터 사진 디테일의 computer zoom에 이르기까지- 익숙한 것을 익숙하지 않은 것, 패턴이나 신비, 결이나 픽셀로 전환시킨다. 이상하고 쓸쓸한, 또한 황폐하나 열정에 찬 아름다움이, 말이 없는 시와 같은, 이정진의 사진에 충만해 있다. 번개처럼 뾰족한 손가락을 가진 파도가 해안으로 밀려와 모래사장에 날카로운 목걸이를 걸어준다. 해골 같은 앙상한 나무들이 파수를 서고, 또 다른 헐벗은 나무들은 폐가의 지붕을 뚫고 무모하게 자라난다. 벽보다 더 오래 지탱하고, 쓸모란 전혀 없어 보이는 유리창이 하늘을 배경으로 솟고 있다. 야생성이 다져진 긴 지평이 사진으로 인하여 잉크 드로잉 같이 보인다. 이따금 이정진의 땅은 수성에서 보내온 사진같이 보인다. 종종 예술가가 그것을 우리에게 설명할 필요가 있지만, 외계적이면서 가치있는 것일 수도 있다는 것을 우리에게 상기시켜준다. 부패는 더 익숙하고 더 급하다. 기우는 집, 맥없이 그러나 막을 수 없이 죽어가는 집 - 엔트로피에 이르는 길에 서 있는 매우 우아한 표지판 같은 것이다. ● 그녀의 프린트는 최선의 재생으로도 전달하지 못할 미묘함과 통렬함을 보여준다. 그녀는 꼼꼼하게 liquid light라고 불리는 감광유제를, 손으로 만든 거친 가장자리를 가진 큰 한지에 11.5X83" 또는 30X57.5" 의 크기로, 발라준다. 그 종이는 하루에 2, 3장 감광할 수 있다. 붓의 획은 구름, 풀, 또는 바위가 되는데, 이는 이정진의 운필의 솜씨이다. 프린트는 표면에 남지 않고 한지에 스며들며, 유제는 대조를 부드럽게 하여 무한한 뉘앙스를 가진 회색 톤을 만들어낸다. 그러나 liquid light는 예측하기 어려워서, 모든 첫 프린트, 모든 둘째, 셋째 프린트의 결과는 항상 예상 외의 것이 된다. ● 이들 사진에서 주제(소재)는 내용에 순응한다. 주제는 산을 삼켜버리고 언덕을 갉아먹는 거대한 안개이거나, 숲을 점령하고 단호한 천사처럼 꾸준히, 조용히 전진하는 구름일 수도 있다. 그 내용은 이정진이 본 것에 대한 반응이며, 그녀의 영혼에서 보내온 속기록이다. ● 사진은 언제나 그 속에 사진가의 무언가를 지니고 있다. - 지성, 철학, 분노, 야심, 심리 같은 것. 스티글리츠(Stieglitz)나 마이너 화이트(Minor White) 같은 사진가는 종이 위에 그들의 감정을, 특히 풍경의 형태로, 재생하려고 공개적으로 시도한 바 있다. 그러나 풍경이 그것을 묘사한 사람의 내적 존재를 재생할 수 있다는 바로 그 생각은 원나라(1270-1368) 시대 동아시아, 특히 중국의 발견이었다. 마이너 화이트(Minor White)는 동양사상에 영향을 받고 이 문제에 관한 로렌스 바이뇬(Lawrence Binyon)의 말을 인용한 바 있다. "중국의 오랜 전통 속에서 풍경화는... 지역적인 것을 우주적인 것에 혼합시키고 영혼의 상태를 반영하게 되었다." 이 개념이 서양에 보급되는 데 상당한 시간이 걸렸지만, 일단 보급이 된 후에는, 풍경이 그 헐벗거나 과장된 표면만을 전달하는 것이 아니라 우리의 가장 깊은 존재에 울려 퍼지는 메시지를 전달한다는 생각이, 예술가와 사진가 뿐 아니라 땅에 귀를 기울이는 모든 사람에게도 퍼져왔다. ● 이정진의 사진 하나를 보면, 피아노는 없고 피아노 건반이 땅 위에 처절히 놓여있다. 뒤범벅이 되고 흐트러진 건반들, 마구 던져진 망치들 - 피아노는 더 이상 음악을 만들지 않으며 만들 수도 없다. 그러나 이정진에게는 음악을 들려준 것으로 생각된다. ■ Vicky Goldberg

- 이정진_wind 07-85

Shorthand Notes From The Spirit ● Landscapes do not literally speak to us, yet the environment is so crucial to our existence, well-being, and cultural identity that we respond as if it sent messages marked "Personal: Open At Once." Perhaps the land sings? Hymns from the ocean, anthems from mountains, love songs, eulogies, dirges … in voices beyond logic, but heard in the bones. It is ourselves we hear, taking the habited and uninhabited earth for a sounding board that amplifies the mute ripples of pleasure and anxiety that are always with us seeking concrete objects to latch onto. ● If built and unbuilt, spoiled and unspoiled landscapes can move us with their silent songs, images of them are powerful surrogates that find their way into the recesses of the mind. Jungjin Lee, born in Korea, is stirred to photograph in places that will never appear in tourist brochures. Her reactions – plangent, melancholy, resonant as a plucked violin string, seldom definable in mere words – turn land and traces of past life, emptiness and natural forces, into landscapes that verge on the subliminal. They are explorations of a mind: her own. She wrote once in an artist's statement, "The images in the Wind series (2004- ) represent my introspective states and thoughts." ● Lee taught herself photography from a book. After graduating from college, she worked for a year photographing for a magazine, then went freelance for two more. Good experience, she says, but it convinced her that photojournalism was not the path for her. During much of the third year, she photographed an old man who lived in total isolation, searching a mountainside for wild ginseng; she was fascinated by how close he came to the difficult task of harmonizing human life and nature. This unassigned story became a book, an exhibition, and a historic document, for no one in Korea hunts wild ginseng any more. The history of photography is full of rescued histories like this one, which time, if unchallenged, would have drowned. ● Shortly after this, in 1988, Lee moved to America. The very air seemed full of heightened energy and freedom: "I could find something here as an artist." While working toward her MA in photography at New York University, it struck her that the students talked more about ideas, whereas in Asia there was more emphasis on the expression of feeling. She was a street photograph at the time – "New York city is a great school," she says – and though the subject was people, she was really looking for something in herself even then, and she felt that photographing others was "kind of like stealing." In her second year, Lee traveled to the Southwest and there in the desert found a spirit that answered to her own. The landscapes gave her at last, access to her feelings and her inner self. ● We experience visual images emotionally before reason decodes them in language.Lee's photographs insist on this. Her picture of an unprepossessing road at the point where it splits into two directions, a patch of pebbles, two grates, and some wobbly white lines, cannot be easily explained as location, pattern, or texture, not to mention meaning. It's as if she had read Archibald MacLeish's Ars Poetica, which ends, "A poem should not mean / But be" Some of Lee's photographs are about … nothing, or nothing much, or nothing worth stopping for, and yet they beat like a heart. ● Her images often seem dimly salvaged from the edge of a dream, or attempts to pierce veiled secrets nature will not willingly give up, though a lens and an eye might probe them. Tuning in to imprecision, ambiguity, the shifting forces of nature, Lee works in bad weather, courting snow, fog, and wind. In certain images, land and sky have misplaced their horizon and become virtually impossible to distinguish: gray merging with gray where lines are obliterated and the unity of all things finally imposes itself on what passes every day for separation. Skies, clouds, seas can dissolve into abstractions before her lens, making puzzles of parts of nature we once thought we knew. ● One of the givens of any camera is that it must cut a fragment out of whatever it regards. If the fragment is small enough, it tends to be unrecognizable. It did not take long for photography to follow the examples of close-ups the cinema produced around the end of the first decade of the twentieth century – excerpts that magnified but did not destroy identity – and then in a sense combine them with painting's newly abstract erasures of identity. Extreme camera close-ups or fragments of almost anything, from electron microscope images to computer zooms into a detail of a photograph, render the familiar unfamiliar, transforming it into pattern or mystery, grain or pixels. ● A strange and forlorn beauty, both desolate and passionate, permeates Lee's photographs: poems without words. Waves come ashore with fingers as pointed as lightning, laying a spiky necklace along a stretch of sand. Bare trees like temporary skeletons keep watch, others relentlessly grow through the roof of an abandoned house. A window that outlived a wall and gave up any pretense to usefulness rears up against the sky. Stretches of land where wildness is tamped down are converted by photography to the semblance of ink drawings. Sometimes Lee's earth resembles photographs from Mars, reminding us that it is possible to be both alien and valuable, though often it takes an artist to explain that to us. Decay is more familiar and more urgent: a drooping house, languidly but unstoppably dying, is a perversely elegant signpost on the road to entropy. ● Her prints are subtle and poignant in ways that even the best reproduction cannot convey. She arduously brushes the photosensitive emulsion called Liquid Light onto large sheets of hand-made, tattered-edge Korean rice paper in sizes of 41.5 x 83" or 30 x 57.5"; she can only manage to sensitize two or three sheets a day. Brush strokes find their way into clouds or grasses or rocks, active evidence of Lee's hand. The prints sink into rice paper rather than staying on the surface, the emulsion softens contrasts, creating infinitely nuanced gray tones, but Liquid Light is unpredictable, and the results of every print, every second and third try, are always unexpected. ● In these photographs, subject is subservient to content. The subject may be a giant fog that eats a mountain and nibbles away the hills, or a cloud that has invaded a forest and advances steadily, softly, like a determined angel. The content is Jungjin Lee's response to what she saw, shorthand notes from her spirit. Photography always has something of the photographer in it – intellect, philosophy, anger, ambition, psychology. Photographers like Stieglitz and Minor White have explicitly tried to reproduce their feelings on paper, especially in the form of landscape. But the very idea that the landscape could represent the inner being of the person who depicted it is an East Asian, specifically Chinese, invention that goes back to the Yuan dynasty (1279 – 1368). Minor White, deeply influenced by Eastern thought, quoted Lawrence Binyon on the subject: "The landscape in the long Chinese tradition … merges the local in the cosmic, and mirrors rather a state of the soul." It took some time for this idea to permeate the West, but when it did, the sense that landscape communicates not merely its bare or extravagant surfaces but messages resonant with our deepest being spread not just to artists and photographers but also to the rest of us when we listen to the land. In one of Lee's photographs, a piano keyboard, bereft of its piano, lies ignominiously on the ground. Its keys smudged and disorderly, its hammers strewn about, it no longer makes music, no longer can. And yet I think it sang to Jungjin Lee. ■ Vicki Goldberg

- 이정진_wind 07-69

- 이정진_wind 07-106

유령의 땅 ● 마음이 상징을 탐색할 때 마음은 이성의 영역 너머 있는 개념들로 인도된다. (칼 융 Carl G. Jung) ● 아무 편견 없이, 아주 순수하게 다가오는 어둠 쪽으로 돌아서라 그리고 그것의 은밀한 목적이 무엇인지 그것이 당신에게서 무엇을 바라는지 알아보라. (Marie-Louise Von Franz) ● (수평선) 그 현란한 캔버스의 덮개는 보기에 아름다웠을 것이다. 벼룩시장의 칸막이는 풀어헤쳐지고 금속 프레임에 묶였을 때 단단한 지구력이 있었으리라. 항상 거기에 존재해 왔던 것처럼 보이면서도 위대한 한국 조선의 도예품의 속성을 가지고 있다. 의도가 없는 아름다움 같은 것. 미학의 생각을 전혀 없이 만든 겸허한 그릇 같이. 캔버스는 백지의 석판(tabula rasa)이며 서예가의 모든 환상도 채워줄 수 있는 공백의 화판 같은 것이다. 이정진은 숙련된 서예가이다. 숙련되고 미리 기획된 서예의 구조가 그녀의 모든 사진을 특징짓는다. 그녀는 수평구도의 넓고 형식적인 힘을 좋아한다. 열린 두루마리가 그녀가 선호하는 형식이다. 그녀 카메라의 파노라마 구조가 벼룩시장 캔버스에 완벽하게 들어맞는다. (기하학) 어떤 사람은 이정진이 구도를 잡을 때 사진가로서의 장점과 독창성을 그녀가 New York에서 조수 역할을 한 바 있는 로버트 프랭크(Robert Frank)의 영향으로 본다. 스위스 태생의 형식주의자이고 미국 사회의 객관적 관찰자였던 로버트 프랭크가 그녀에게 무엇을 가르쳐줄 수 있었을까? 그렇게 유사성이 없는 기질을 가진 두 사람은 일찍이 없었을 것이다. 다만 로버트 프랭크와 이정진은 사진에 대하여 말이나 글을 쓰지 않을수록 더 좋다는 데에는 의견이 일치했을 것이다. 한국에서의 예술훈련에 이어 이정진은 미국에서 사진 공부를 하면서 10년을 보냈다. 그녀는 미국 주민보다는 주변화된 미국의 공간에 매료되었다. 미국 서부의 사막을 여행하면서 그녀는 수평선, 폐기로 인하여 전환된 장소와 끝이 없어 보이는 공간을 자신이 좋아한다는 것을 확인하였다. Frank는 대조적으로 도시의 보도 위에 안전하게 머물렀다. 그럼에도 불구하고 이정진은 그를 스승으로 흠모한다. 로버트 프랭크의 흑과 백의 연구는 추상표현주의 그림에서 다소 영향을 받았을 것인데, 특히 그 구조가 동양의 서예를 상기시키는 프랭크 클라인(Frank Kline)의 그림 속 흰 들판을 배경으로 한 검고 허리띠 같이 생긴 형태를 닮았다. 이정진의 디자인 감각에 로버트 프랭크가 준 영향이 있었다면, 다름 아니라 그녀가 어려서부터 실제로 서예를 실습하면서 터득한 바를 일층 강화하였을 것이다. (진동) 벼룩시장 캔버스의 형태는 그 주변에 깔려있는 신비를 해명하지 못한다. 거대한 수평구도를 접근하면서 이정진은 북처럼 팽팽한 덮개를 건드리는 바람을 발견한 것이다. 그녀는 그 진동이 교묘하고 거의 보이지 않았으며 거의 들리지 않는 소리와 같은 것이었다고 말한다. 그녀는 그것의 "비밀", 신비한 에너지의 흐름에 마음이 흔들렸다. 보통 사물로 하여금 2중의 삶을 살도록 하는 자연의 교묘한 힘에 감응한 사람은 그녀가 처음이 아니다. 태고로부터 아시아시인들은 바람의 많은 계절과 표정을 파악하였다. 동요되지 않는 관찰자인 그들은 바람이 말없는 나무 무더기를 노래하게 하는 때와 같이 이상함 속에 담겨진 아름다움을 받아들였다. 일본 시인 고바야시 이사(Kobayashi Issa)는 바람을 말하지 않고, 대신 벽에 난 구멍이 피리를 분다 이 가을 저녁. 이라고 읊조렸다. 폐허의 건축을 통과하는 바람이 Issa로 하여금 이 하이쿠를 쓰게 했다. 가볍게 뛰고 있는 캔버스 위의 바람 에너지의 리듬은 이정진의 정신 집중의 고른 숨결을 반향하였다. 그것은 "내게 아직도 신비로운" 그런 감정을 일으켰다. 바로 이러한 순간 이정진은 셔터를 누르는 것이다. (호흡) 바람은 변하기 쉽고 불안정하다. 그것은 무심하고 맹목적으로 난폭하다. 성경의 시편과 코란에서 바람은 신이 보낸 천사 전령이다. 또한 성령이다. 힌두교 상징으로서 바람은 하늘과 땅 사이에 있는 "교묘한 세계" 즉 호흡의 공간을 지배한다. 우리는 팽팽한 벼룩시장을 거대한 호흡기관인 횡경막으로 볼 수 있다. 인체의 늑골 아래 있는 평평하고 질긴 근육인 횡경막은 폐에 공기를 보내준다. 그 움직임은 심장 박동과 같이 거의 자동적이다. 호흡조절에 관한 고대 학문인 호흡학에 있어서 인도의 요가수행자는 우주적 원리인 하나의 힘을 발견하였다. 그들은 그것을 산스크리트어로 prana, 즉 절대에너지라 불렀다. Prana는 단순한 숨이 아니다. 그보다 훨씬 신비하고 비교적이며, "중력, 전기, 행성의 운행, 또한 가장 높은 것에서 가장 낮은 형태의 모든 생명에 있어서의 모든 운동, 힘 또는 에너지의 진수이다." Prana는 어디에든 있다. 그것을 잡기 위하여 정신적 구도자는 호흡에 집중하면 된다. 규칙적 호흡에 실려다니는 prana는 바람의 한 변종으로 보이지만, 요가수행자들은 다르게 설명한다. 물질도 대기도 아닌 prana는 그것들에 내포되어있는 강력한 원리이다. 그것은 대기가 닿지 못하는 곳에 파고든다. 히브리 사람들은, 사람의 상식을 거역하는 그것의 신과 같은 이질성을 두둔하면서, "살아있는 정신의 호흡"이라고 불렀다. Prana는 몸, 숨, 신경에 저장될 수 있다. 제대로 개발하면, 그것은 정신력을 강화하고, 육체적, 정신적 건강을 증진한다. 이정진은 요가, 호흡 훈련, 또는 어떠한 "이론적"인 수행이, 자기의 작업이나 자기 작업의 해석 방법과 연관되어 있다는 의견을 거부한다. 이정진은 자신이 받았던 서예와 도예 교육을 사진작품과 연관시키려는 사람을 더 이상 용납하지 않는다. 본격적인 정신수행자가 아닌 예술가로서 그녀는 무심의 영역을 피력하는데, 이는 자기 머리 속의 소음을 잠재우고 상습적, 물질주의적 사고에서 오는 방해를 제거하려고 노력하기 때문이다. 그녀는 사진을 찍는 행위를 둘러싼 충전된 분위기를 "내 자신 속의 저 '절대적' 메아리가 무한 시공을 지나가는 순간"으로 묘사한다. 이정진의 내부의 절대적 메아리는 prana의 절대적 에너지일 수 있다. 무한성의 도착보다 더 신비한 것은 없다. 바로 이것이 그녀가 WIND의 영상들이 그려내기를 바라는 것이다. (만다라) 그녀가 거대한 캔버스를 촬영하였을 때 바람은 하나의 사실이었다. 그러나 그녀는 우리가 그것을 보도록 허용하지는 않았다. 이정진이 캔버스로 사진프레임을 채웠기 때문에 우리는 그 비밀의 힘을 느끼는 것이다. 그것은 하나의 표적, 초점지역처럼 작용한다. 묘사를 초월하는 그것은 자신의 논리를 가진 상징이다. 만다라처럼 그것은 "그림"이라는 개념을 심령적 지도로 대체하며, 이 윤곽은 집중을 통하여 말없는 관중을 흡수하여 감각기관 너머의 세계로 인도한다. 이정진은 이 특정한 사진이 어떻게 그녀로 하여금 이 시리즈에 있는 모든 사진작품을 WIND로 부르게 했는지 설명하지 못한다. 그것은 감정, 순수한 육감이었다. 그녀는 New Mexico, Texas, California, Canada와 한국의 장소들과 사물들을 단순히 기록한 것은 아니다. 그들을 통하여 그녀는 달리 표현할 수 없는 에너지를 보이게 만들 수 있음을 발견한 것이다. Prana는 대기가 도달하지 못하는 곳에 침투하는 것이다. 아마도 이 때문에 어느 사진에도 격정을 씻어내는 바람이나, 물질계에 대한 바람의 뼈를 찌르는, 침식적 또는 조형적 효과가 보이지 않는다. 흔히 사진적 의미에서의 "순간"이 없는 것이다. 바람에 실려오는 향기를 암시하기 위하여 꽃피는 나무가 꽃잎을 흐트리는 경우는 없다. 곡간이 무너지고, 자동차가 부식하고, 시골 식당의 지붕에서 나무가 튀어나오고, 버려진 학교 버스가 수평선에 나타나고, 외로운 개들과 가축이 광활하고 황폐한 공간을 점철한다. 그들은 바람의 작용과는 아무 상관이 없다. 태고의 만다라에서처럼, 프레임 안의 모든 것이 해명되고 정연한 기하학적 구도 속에 담긴다. 방관과 망각의 느린 과정 속에서 시간은 변형된다. 보통 사물들이 슬프고 이상한 것이 된다. 그것은 빛의 각도에 달려있다. 본래의 기능을 상실한 보통 반사경은 검은 들을 배경으로 맥박처럼 뛰는 거대한 원반이 된다. 벼룩시장의 캔버스를 응시할 때 우리는 이 만다라를 응시하게 된다. 다른 세계의 것처럼 이해할 수 없는 그것은 내부를 가리켜준다. (그림자) 외부세계의 사물 너머 있는 더 큰 힘에 항복하도록 이정진은 우리에게 요청한다. 움직이는 구름은 어떤 사진들을 침공한다. 그녀는 프레임을 어떤 묘사도 거부하는 검은 날씨 덩어리로 채운다. 이들 형태는 정신의 충격 즉 천지 사이에 있는 절묘한 세계를 가리킨다. 그들은 보이지는 않으나 도처에 현존하는 것들을 상징한다. 검은 사진의 숯으로 먹칠한 효과는 융 심리학이 "유령의 땅" 또는 무의식으로 묘사하는 것들에게 형태를 주고, 잠재적 풍요와 점차적 각성의 놀라운 상태를 주어, "사람으로 하여금 달이 비치는 풍경 속 같은 상황에 있게 한다." 모든 내용이 흐려지고, 서로 합쳐지면, 무엇이 어디 있는지를 확실히 모르게 되고, 어떤 것이 어디서 시작되고 끝나는지 모르게 된다. 융 학파의 심리학자들은 이 지대를 그림자(shadow)라고 부르는데, 우리 자신 속에서 우리가 통상 등한히 하는 선악의 모든 요소를 지칭하는 것이다. "그림자가 우리의 친구 또는 적이 되는가는 주로 우리 자신에 달려 있다. 그림자는 무시되거나 오해될 때 적대적이 된다." 그림자의 암흑 세계는 항해의 문제를 제기할 수 있으나, 그것과 정면으로 대결하게 되면 더 완전한 자기인식을 얻을 수 있다. "그것의 은밀한 목표가 무엇이고, 당신에게서 무엇을 원하는지 알아보라."고Marie-Louise Von Franz는 권고한다. 이정진의 혼미한 암흑은 이 비옥한 유령의 땅에 연관되어 있다. 벼룩시장의 캔버스도 그렇다. WIND의 모든 영상도 그렇다. 각각은 우리가 "우리에게서 무엇을 원하는가?" 라는 질문으로 응답하게 되는 그런 종류의 질문인 것이다. (변화) 한국인은 바람이라는 단어를 바람(희망)과 연결시킨다. 한국어로 "바람"은 바람과 희망을 의미한다. 태고로부터 소망을 가진 사람들은 주역이라는 고대 중국의 역술법에 질문을 던져왔는데 거기에서 바람(wind)은 57번째 6괘이다. 주역은 어느 특정한 종교, 컬트, 또는 학파에 속한 일은 없다. 바람(wind)이라는 문자를 암호적으로 해석하는데 중요한 것은 그것이 바람의 물리적 특성을 지칭하는 것이 아니라는 사실이다. 이정진이 주역을 모르고 있다 하더라도, 그녀의 사진은 바람(wind)을 그와 유사하게 사용하고 있는데, 말하자면 내면의 균형을 증진하는 보이지 않는 개념으로 사용하고 있다. 주역의 설명에 따르면, "바람은 작지만 발전적이다." , "바람은 침투이고 몸을 낮추는 것이다.", "그것은 유연한 복종을 통하여 목적을 성취하는 겸양의 길이다." 이것은 집요함을 통하여 점차적으로 침투하는데 늦추지 않고 일하며, 충족의 단계에서 멈출 줄 아는 지혜이다. 이것이 이정진의 방법이다. 겸손하게, 형태가 없는 지역을 의식하면서, 그녀는 작품 소재의 진실에 순응한다. 무형(공)과 무심은 파악하기 어렵다. 따라서 불교도나 정신적 구도자는 안내자, 보살, 불교적 도의 스승, 즉 모든 사물의 절대적 불가지성을 육감으로 납득하는 경지에 도달한 선생이 필요한 것이다. 사진작업을 하면서 이정진은 자신의 보살이 된다. WIND의 모든 영상은 하나의 묘사를 넘어 똑같은 요청을 한다. "보통 사물을 보고, 변화를 사랑하고, 절대적 불가지성을 납득하라." 속세를 명상하고, 천상적인 것을 인식하라. 네루다(Pablo Neruda)는 시인이 된 연유를 이렇게 회상하였다. 그리고 나, 이 작은 존재 방대한 별이 빛나는 허공(공), 유사성, 신비의 영상에 취해, 나 자신이 그 심연의 순수한 일부라고 느껴졌다. 나는 별들과 같이 운행하였다 나의 가슴은 바람과 함께 풀려났다. ■ Eugenia Parry

- 이정진_wind 07-84

As the mind explores the symbol, it is led to ideas that lie beyond the grasp of reason.(Carl G. Jung) (Carl G. Jung, "Approaching the Unconscious," Man and his Symbols, edited and with an introduction by Carl G. Jung, New York, Dell Publishing Company, 1964, p. 4)

...turn directly toward the approaching darkness without prejudice and totally naively, and try to find out what its secret aim is and what it wants from you. (Marie-Louise Von Franz) (Marie-Louise von Franz, "The Process of Individuation," in Man and His Symbols, p. 170)

Horizon ● It must have been beautiful to see, that extravagant sheath of canvas. Only a flea-market partition, unfurled and lashed to a metal frame, it was tough and time-worn. Seeming always to have existed, it shared that attribute of the great Yi-dynasty ceramics of Korea: Beauty without intention. Rough, humble vessels made without the least thought of aesthetics. ● The canvas was a tabula rasa, a blank slate that would have fulfilled any calligrapher's fantasies. Jungjin Lee is a trained calligrapher. Calligraphy's disciplined, pre-meditated structures distinguish all her photographs. She loves the broad, formal strength of horizontals.(Born in South Korea in 1961, the youngest of five, Jungjin Lee startled her business-minded family by mastering calligraphy as a child. At Hong-Ik University in Seoul she majored in ceramics.) The open scroll is her preferred shape. Her camera's panoramic format held the flea-market canvas perfectly.(Jungjin Lee used a mid-sized panoramic Linhof 612 camera for the Wind series. In the darkroom she coated Hanji, a Korean paper with Liquid Light, which allows her enlarge the image to the size she wants.) Geometry ● Some credit Jungjin's strength and originality as a photographic composer to the influence of photographer Robert Frank, whom she assisted in New York. What could Frank, a Swiss-born formalist and detached street-observer of American social ritual, have taught her? There aren't two more dissimilar temperaments, except that Robert Frank and Jungjin Lee would agree that the less said and written about photography, the better. After her artistic training in Korea, Jungjin spent ten years in America studying photography. She was attracted to the marginalized American spaces, not to their inhabitants. Traveling through the deserts of the American West deserts confirmed her pleasure in horizons, in places transformed by neglect, and in seemingly limitless space. Frank, by contrast, stayed safely on the urban pavement. Nonetheless, she reveres him as a master. Frank's investigation of black and white owes something to the paintings of Abstract Expressionism, notably, the black, girder-like forms against white fields in the paintings of Franz Kline, whose structuring recalls oriental calligraphy. Frank's influence on Jungjin's sense of design would only have reinforced what she had learned from childhood by actually practicing and mastering calligraphy. Vibration ● The form of the flea-market canvas doesn't account for the mystery surrounding it. Approaching the grand horizontal, Jungjin discovered wind playing the taut sheath as if it were a drum. The vibrations were subtle, she said, hardly visible, as were the sounds, barely audible.(From my conversations with Jungjin in May 2009. Henceforth, direct quotes from the artist or paraphrases of her words during these exchanges will be cited in the Notes as Conversations.) She was stirred by "the secret" of it, by a mysterious flow of energy. She isn't the first to respond to the uncanny way natural forces will invite ordinary things to live double lives. Asian poets, through the ages, have catalogued many seasons and expressive guises of the wind. Imperturbable observers, they accepted the beauty in strangeness, as when wind made mute piles sing. Japanese poet Kobayashi Issa didn't mention wind. Instead he noticed that ● The holes in the wall play the flute this autumn evening. (Kobayashi Issa (1783-1827) in The Essential Haiku, Versions of Bashō, Buson and Issa, edited and with verse translations by Robert Haas, Hopewell, N.J., The Ecco Press, 1994, p. 185.) ● Wind traveling through ruined architecture inspired Issa to write this haiku. The rhythm of wind energy on gently palpitating canvas echoed the even breathing of Jungjin's concentration. It touched feelings which remain "a mystery to me."(Conversations) That's when she pressed the shutter. Breath ● Wind is fickle and unstable. It stands for empty-headedness and blind violence. In the Book of Psalms and the Koran, wind is a messenger angel from God. It is the Holy Spirit. In Hindu symbolism, wind rules the "subtle world" which lies between Heaven and Earth, the space of breath.(Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrant, The Penguin Dictionary of Symbols, translated by John Buchanan-Brown, London, Penguin Books, 1996, pp. 1110-1111.) One could conceive of the taut flea-market as a huge diaphragm, instrument of breath. The diaphragm, a flat, tough muscle, below the ribs of the body, sends air into the lungs. Its motion is almost as automatic as that of the beating heart. In the science of breath, the ancient discipline of regulated breathing, the yogis of India identified a force that became a universal principle. They called it prana, in Sanskrit, Absolute Energy. Prana is not breath. Far more mysterious and esoteric, it is ". . . the essence of all motion, force or energy. . . in gravitation, electricity, the revolution of the planets, and all forms of life from the highest to the lowest." Prana is everywhere. The spiritual seeker has only to concentrate the breath in order to capture it. Borne on regular respirations, it seems like a variable of wind, but the yogis characterize it differently. Neither matter nor air, prana is a potent principle, contained within them. It penetrates where air cannot reach. The Hebrews called it "the breath of the spirit of life," affirming a God-like otherness that confounds ordinary knowing. Prana can be stored in body, brain, and nerves. Properly cultivated, it strengthens psychic powers, promotes greater physical and mental health.(Yogi Ramacharaka,"The Esoteric Theory of Breath," in Science of Breath, A Complete Manual of the Oriental Breathing Philosophy of Physical, Mental, Psychic and Spiritual Development, Chicago, Yogi Publication Society, 1904, pp. 18-22.) Jungjin Lee resists suggestions that yoga, trained breathing, or any "theoretical" practices might relate to the way she makes her work, or how it might be interpreted. She no longer abides anyone trying to connect her early formation through calligraphy and ceramics to the appearance of her photographs. As an artist, not as an overt spiritual seeker, she claims the territory of no-mind because she makes an effort to silence the chatter in her head and eradicate the obstructions of habitual, materialist thinking. She describes the charged atmosphere around taking a picture as a moment when "that 'absolute echo' within myself travels through infinite time and space."(Extract from a draft of Jungjin Lee's written statement about the WIND series.) The absolute echo within Jungjin may be prana's absolute energy. Nothing is more mysterious than the arrival of the infinite. This is exactly what she wants the WIND images to portray. Mandala ● Wind was a fact when she photographed the huge stretch of canvas. But she hasn't allowed us to see it. We feel the force of the secret because Jungjin filled the frame with the canvas. It acts like a target, a field of focus. Surpassing description, it is a symbol with its own logic. Like a mandala, it replaces the idea of "picture" with a psychic map, a configuration which, through concentration, absorbs the silent viewer and leads to worlds beyond the senses. Jungjin can't explain why this particular photograph led her to call all the photographs in the present series WIND. It was a feeling, pure intuition. She did not simply document places and things in New Mexico, Texas, California, Canada, and Korea. Through them, she discovered she could make otherwise inexpressible energy visible: prana penetrates where air cannot reach. Perhaps this is why there is no evidence in any of the photographs of passion-cleansing wind, or wind's bone-combing, corrosive, sculpting effects on the material world. There are no moments in the usual photographic sense. No flowering trees scatter petals to suggest wind-borne fragrance. Barns have collapsed, automobiles have eroded, trees protrude from the roof of a rural restaurant, an abandoned school bus traces the horizon, lonely dogs and cattle dot vast, arid spaces. They have nothing to do with wind action. As in ancient mandalas, everything in the frame is accounted for, locked into disciplined geometry. In the slow process of neglect and forgetting, time transforms. Ordinary things become sad and strange. It depends on the angle of light. An ordinary reflector deprived of its original function is a huge pulsing disk against a black field. We fix on this mandala, as we fix on the flea-market canvas. Otherworldly, incomprehensible, it points within. Shadow ● Jungjin asks us to surrender to greater powers beyond the contemplation of externals. Moving clouds invade some of the photographs. She filled other frames with masses of black weather that defy any kind of describing. These configurations allude to the impact of spirit: the subtle world between Heaven and Earth. They symbolize what cannot be seen, and yet is everywhere present. The smeared charcoal-smudged effect of the black pictures gives form to what Jungian psychology describes as the "ghost land,"(Marie-Louise Von Franz, "The Process of Individuation," Man and His Symbols, p. 186. Through shamanistic rituals and deliberately induced dream states, males from Eskimo and other arctic tribes summoned what they called the "ghost land" or anima (the domain of the feminine). Von Franz understood "ghost land" as equal to the unconscious.) or the unconscious, a puzzling state of potential richness and gradual awakening where ". . . one is unfortunately in the same situation as in a moonlit landscape. All the contents are blurred and merge into one another, and one never knows exactly what or where anything is, or where one thing begins and ends."(Ibid, p. 183.) Jungians call this realm the shadow, meaning everything, good and bad, in the self that we ignore. "Whether the shadow becomes our friend or enemy depends largely on ourselves. . . . The shadow becomes hostile only when he is ignored or misunderstood."(Ibid, p. 182.) The darkling world of shadow may present a navigational problem, but confronting it promises more complete self knowledge. "Try to find out what its secret aim is and what it wants from you," Marie-Louise Von Franz advised.(See Note 2.) Jungjin's masses of obscuring blackness allude to this fertile ghost land. So does the flea-market canvas. So do all the images in WIND. Each is a question to which we respond with another question: what do you want from us? Change ● Koreans join the word wind to aspiration. Baram, in Korean, means both wind and hope. Through the ages, hopeful aspirants have brought questions to the ancient Chinese divining tool, the I Ching, (Book of Change) where Wind is number 57 of the hexagrams. The I Ching has never belonged to any particular religion, cult, or school of thought. What is significant in the cryptic interpretation of the Wind character is that it doesn't refer to the physical characteristics of wind itself. Jungjin doesn't know the I Ching, but her photographs use wind similarly, as an invisible concept that promotes inner balance. "Wind is small but developmental," the Book's explanation goes. "Wind is penetration and laying low." It is a yielding path of humility that succeeds through flexible obedience. This penetrates gradually through persistence, by working without slacking off, by knowing to stop at sufficiency.(The Taoist I Ching, translated by Thomas Cleary, Boston, Shambhala Publications, Inc., 1986, p. 210.) This is Jungjin's method. With humility she yields to the truth of her subjects, mindful of realms where there is no form. No form (Void) and no mind are difficult to grasp. This is why Buddhist, spiritual seekers need a guide, a bodhisatva, teacher of the Buddhist way, who has "attained the intuitive tolerance of the absolute incomprehensibility of all things."(The Holy Teaching of Vimalakirti, translated by Robert A. F. Thurman,) Photographing, Jungjin is her own bodhisattva. Every image in WIND, more than a depiction, makes the same requests: view ordinary things, love change, tolerate absolute incomprehensibility. Contemplate the temporal, recognize the celestial.—Pablo Neruda remembered how he became a poet. And I, tiny being, drunk with the great starry void, likeness, image of mystery, felt myself a pure part of the abyss. I wheeled with the stars. My heart broke loose with the wind.(Pablo Neruda, from "Poetry," in the series of poems, Where the Rain is Born, collected in Isla Negra, A Notebook, translated from the Spanish by Alastair Reid, New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1981, p. 33.) ■ Eugenia Parry

Vol.20100205d | WIND-이정진 사진집 출간 기념회